Jens Knigge »

Platinum Prints

Exhibition: 6 Sep – 8 Nov 2014

Fri 5 Sep 18:00 - 21:00

Johanna Breede PHOTOKUNST

Fasanenstr. 69

10719 Berlin

+49 (0)30-88913590

photokunst@breede.de

www.johanna-breede.com

Tue-Fri 11-17, Sat 11-14

Jens Knigge

"Platinum Prints"

Exhibition: 6 September ‐ 8 November 2014

Opening: 5 September, 6-9pm

The Finest Shades of Gray

When a contemporary photographer is interested in such an archaic technique as the platinum-palladium print in our age of digital imagery, he must have a good reason: for Jens Knigge it is likely the rich gray tonal scale which can only be achieved in this process. As Irving Penn before him, Knigge has perfected the entire production process as few others have, starting with releasing the shutter of his large-format camera, to the work he later performs in the darkroom. In his case photography is not only an artistic and creative approach to the subject and the camera, but also simple craftsmanship. The production and elaboration of the prints takes time, patience and experience. Not every print turns out or meets the high demands of the photographer, who ultimately produces editions in a small number of prints.

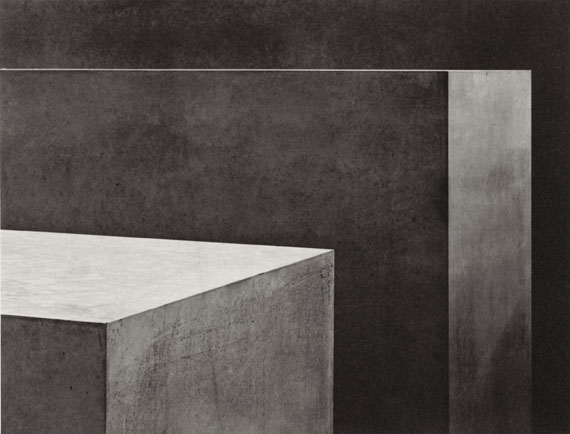

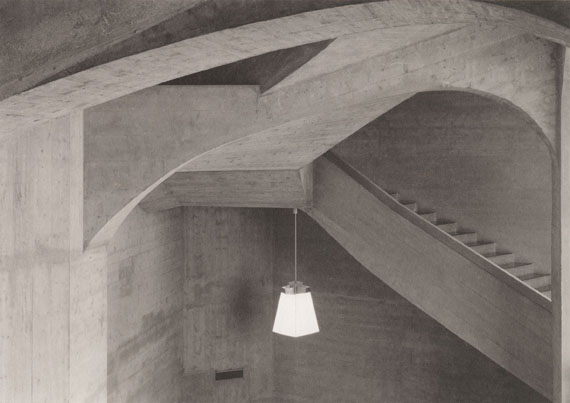

The technique is solely a tool to underpin or reinforce the photographed subject. The picture surface is mat and the platinum is not on, but rather embedded in the paper fiber. The haptic nature of the photographic paper and the image itself creates the illusion of three-dimensionality: a stone stairway and a handrail on the stairs or a white lamp hanging in a room can be experienced spatially. Knigge's images are reduced and at times even sparse. He has an exceptional sense for light and shadow as well as for material and space. Occasionally he selects architectural details in such an extreme close-up that a purely two-dimensional structure emerges, which is simultaneously a study of material as well as surface. The well-known, representative buildings which he depicts cannot always be recognized inasmuch that the photographer is interested in a specific architectural type, as well as a general abstract image language. If one knows the location where the image was taken, such as Schinkel's Altes Museum in Berlin, then the crumbling edges, the holes and the repairs made on the columns turn into traces of time which point to the battles during World War II and which, after later careful restoration, were kept visible intentionally to this day. Jens Knigge thus shows us damaged building surfaces in subtle, timeless close-ups. Berlin is a city with an immense history and has undergone many metamorphoses so that slightly scratching the surface facade brings a previous layer to light. Again the following applies: only those who are aware of the past can understand the present.

The Goetheanum presents a slightly different case: Rudolf Steiner planned and built this unusual concrete solitaire as an anthroposophic center in Dornach, Switzerland in the 1920s. Knigge congenially transposes the expressionistic concrete structure within the mid-tones of his timeless platinum prints. Some prints also resemble graphite drawings. One image shows a facade protruding and receding at many points and which seems to have no angles. The window at the center of the image does not allow the viewer to see the interior, but rather reflects the trees and the sky. In this image Knigge lets nature and culture clash strongly against one another while simultaneously connecting them. In the Goetheanum the photographer also skillfully translates the space of the entrance hall into the spatial illusion of a two-dimensional picture.

Concrete also interests contemporary architects and artists as a building material and its use in facade structures. For example Axel Schulte's crematorium built in Berlin-Treptow in the mid -1990s or Peter Eisenman's Holocaust Memorial finished in 2005. Knigge also photographed the latter structure shortly after its completion. He reduced some of the more than 2000 stelas, within a small detail and without any reference scale, to basic geometric forms in differentiated gray tones, in short: a formal abstraction. Today, with its heavy concrete cubes bearing sharp edges and smooth surfaces and with thousands of visitors daily, the Memorial is a part of history much like the majestic stillness inherent in Knigge's photographs.

Knigge additionally confronts us with an interesting point of contemplation. Some time ago he discovered that large-format X-ray negatives had the correct density to be processed as platinum prints. He thus acquired negatives such as a broken elbow reinforced with steels pins or a kneecap held together with metal wire and transformed them as contact copies into abstract photographic prints. This appropriation art, however, remains so unique and exceptional in his work that usually many highly concentrated and complex work stages are involved in making the final print.

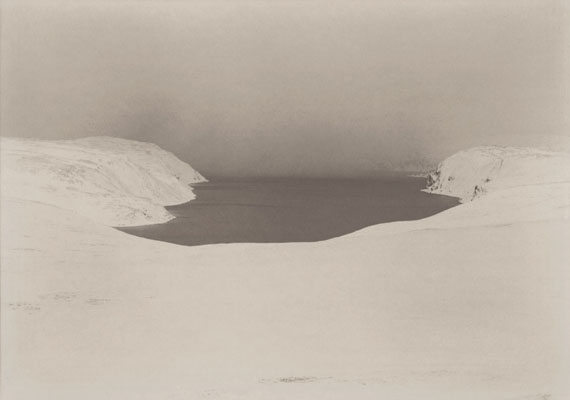

The current exhibition at Galerie Johanna Breede presents architecture and landscapes, still lives and X-rays - a very heterogenic as well as interesting mix which offers insight into Knigge’s artistic production over the past 15 years. He often finds his subjects in Berlin and presents us with examples of outstanding architecture. His specific view for architectural detail and the surface of the materials of buildings rather than the whole object set him apart from the traditional architectural photographer.

Matthias Harder�

Jens Knigge

"Platinum Prints"

Ausstellung: 6. September bis 8. November 2014

Eröffnung: 5. September, 18 – 21 Uhr in Anwesenheit des Künstlers.

Wenn ein zeitgenössischer Photograph sich in der Hochphase digitaler Bildwelten bewusst für eine so altertümliche Technik wie die der Platin-Palladium-Prints interessiert, muss er schon einen triftigen Grund haben: Für Jens Knigge ist es wohl das reiche Grauwertspektrum, das nur auf diesem Weg erreicht werden kann. Den Produktionsprozess vom Auslösen seiner Großbildkamera bis zur Dunkelkammerarbeit hat Knigge – wie Irving Penn vor ihm – perfektioniert wie kaum ein anderer. Photographie ist hier nicht nur ein künstlerisch-kreativer Umgang mit Motiv und Kamera, sondern auch schlichtes Handwerk. Die Herstellung, ja Erarbeitung der Werke braucht Zeit, Geduld und Erfahrung. Nicht jeder Abzug gelingt beziehungsweise genügt den hohen Ansprüchen des Photographen, der schließlich Editionen in kleinen Auflagen produziert.

Die Technik ist stets nur Hilfsmittel, um das photographierte Motiv zu unterstützen oder zu überhöhen. Der Farbauftrag ist matt, die bilderzeugende Farbe befindet sich nicht auf, sondern in der Papierfaser. Die Haptik des Photopapiers, ja selbst der Darstellung führt zur Illusion einer Dreidimensionalität: Eine Steintreppe und ein Handlauf an dieser Treppe oder eine im Raum hängende weiße Lampe werden räumlich erfahrbar. Knigges Motive sind reduziert, mitunter karg. Er hat ein ausgeprägtes Gespür für Licht und Schatten, für Material und Raum. Gelegentlich wählt er Architekturdetails so nahansichtig, dass eine flächige All-Over-Struktur entsteht, die zugleich Material- und Oberflächenstudie ist. Nicht immer können wir die berühmten Repräsentationsbauten erkennen, insofern geht es ihm vermutlich auch um einen bestimmten Architekturtypus sowie um eine abstrahierende Bildsprache im Allgemeinen. Weiß man um den Aufnahmeort, etwa Schinkels Altes Museum in Berlin, werden die Bruchkanten, Löcher und Ausbesserungen in den Säulenkanneluren zu Zeitspuren, die auf die Frontkämpfe im Zweiten Weltkrieg verweisen und nach einer späten, behutsamen Sanierung bis heute bewusst sichtbar geblieben sind. So zeigt uns Jens Knigge versehrte Gebäudeoberflächen in subtilen, zeitlosen Nahansichten. Berlin ist eine Stadt mit so viel Geschichte und Metamorphose, dass man gewissermaßen nur an der Fassade zu kratzen braucht, um eine frühere Schicht zum Vorschein zu bringen. Auch hier gilt: Nur wer die Vergangenheit kennt, versteht die Gegenwart.

Beim Goetheanum liegt der Fall etwas anders: Rudolf Steiner plante und erbaute in den 1920er-Jahren im schweizerischen Dornach diesen außergewöhnlichen Betonsolitär als Anthroposophisches Zentrum. Und Knigge setzt heute den expressionistischen Sichtbetonbau kongenial in die Mitteltöne seiner nur schwer zu datierenden Platinprints um. Manche Abzüge wirken überdies wie Graphitzeichnungen. In einer Aufnahme blicken wir auf die an vielen Stellen vor- und zurückspringende Fassade, die ohne rechte Winkel auszukommen scheint. Das Fenster im Bildzentrum lässt uns jedoch nicht nach innen blicken, sondern es spiegelt Bäume und den Himmel. Hier lässt Knigge Kultur und Natur hart aufeinanderprallen – und verbindet die Bereiche zugleich. Auch im Goetheanum übersetzt der Photograph die Räumlichkeit der Eingangshalle geschickt in die räumliche Illusion eines zweidimensionalen Bildes.

Beton als Werkstoff und Sichtfassadenmaterial interessiert bekanntlich auch zeitgenössische Architekten und Künstler, man denke etwa an Axel Schultes Mitte der 1990er Jahre erbautes Krematorium in Berlin-Treptow oder an Peter Eisenmans 2005 eingeweihtes Holocaust-Mahnmal. Auch dort photographierte Knigge. Einige der mehr als 2000 Stelen reduzierte er im engen Bildausschnitt und im Verzicht auf jeglichen Größenmaßstab zu geometrischen Grundformen in ausdifferenzierten Grauabstufungen, kurz: zu einer formalen Abstraktion. Die scharfen Kanten und glatten Flächen der tonnenschweren Betonquader, hier aufgenommen kurz nach der Einweihung des Mahnmals, sind heute, bei täglich Tausenden von Besuchern, ebenso Geschichte wie die geradezu majestätische Ruhe, die Knigges Aufnahmen noch innewohnt.

Schließlich konfrontiert er uns mit einer interessanten Introspektion. Vor einiger Zeit entdeckte er, dass großformatige Röntgenaufnahmen die richtige Dichte besitzen, um ebenfalls als Platinprint verarbeitet werden zu können. Und so eignete sich Knigge solche Negative eines gebrochenen, mit Stahlstiften verstärkten Ellenbogens oder einer durch Metalldrähte gefestigten Kniescheibe an und transformierte sie als Kontaktkopie in wiederum abstrakte photographische Abzüge. Diese Appropriation-Art bleibt jedoch so eigenständig wie ungewöhnlich in seinem Werk, das normalerweise von der Aufnahme eines Motives bis zur Dunkelkammer in mehreren hochkonzentrierten und ebenso komplexen Arbeitsschritten zum Bild umgesetzt wird.

In seiner aktuellen Ausstellung in der Galerie Johanna Breede sehen wir Architektur und Landschaft, Stillleben und Röntgenbilder, eine so heterogene wie spannende Mischung, ein Einblick in das künstlerische Schaffen der vergangenen 15 Jahre. Die Motive findet Jens Knigge häufig in Berlin. Er präsentiert uns Beispiele herausragender Architektur, sein enggefasster Blick für das architektonische Detail und die Materialoberflächen der Gebäude abstrahiert von der Totale und insofern von der Arbeit eines traditionell arbeitenden Architekturphotographen. (Matthias Harder)

�