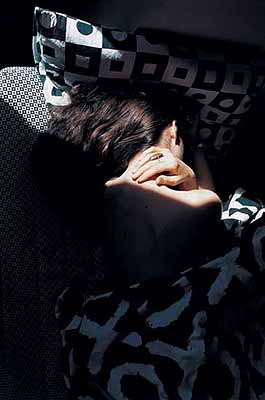

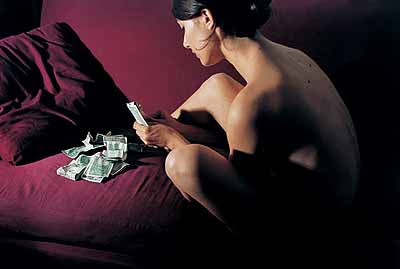

Elinor Carucci »

Closer

Exhibition: 27 Mar – 30 Apr 2004

Noga Gallery of Contemporary Art

60 Ehad Ha'am St.

65202 Tel Aviv

+972 3 -5660123

nogaart@zahav.net.il

www.nogagallery.com

Mon-Thu 11-18 . Fri , Sat 11-14

My mother was the first person I ever photographed and I still take pictures of her obsessively. Quite literally, in more than one way, she was - she is - my natural point of origin. My connection to the world. I used to think that the struggles with her, as well as the sense of closeness, security and warmth, the whole way I related to her during childhood, would somehow naturally end with the end of childhood. Perhaps they were transformed, elevated to other levels. But in many ways, they never lost their power over me. I started taking pictures of her when I was fifteen. I used my father's old Canon camera. Gradually, in concentric circles, the subjects of my work expanded. From my mother, to my father and brother, to the extended family, until, in recent years, the center shifted, at least partially, to my husband, Eran. I no longer see my mother only as a strong person, she is no longer my only source of security, of power, of beauty, but I do measure my own femininity, my own self, as a distance from her. When she prepared me for the world, she showed me the world through her eyes. It was, or is, a long process. When I was twenty-two she put lipstick on my lips, her lipstick. This was one of many things that were both, somehow, continuity and separation. My own femininity, yet always drawing on hers. Oddly I still felt her lipstick would somehow protect me. But this closeness was, in a way, also what enabled me to move away, to enlarge the circles of both life and work, and finally to shift much of the focus to Eran, even to myself. The camera was, in this sense, both a way to get close, and to break free. It was a testimony to independence as well as a new way to relate. A boundary, a distance, as well as the documentation of closeness. I could see my mother, my husband, my father, at once in a detached and a related way. In the first few years I was mostly intuitive, even impulsive, in the way I shot. After a while, however, I tried to turn to what I thought of then as more professional photography. I began shooting series of black and white pictures, my mother and myself as their subjects. They were structured, posed: Mother looked too ready to be in a photograph, well prepared, presenting herself to me. It's not that we weren't candid or open. We were, and we did try to recreate real scenes, actual situations. But something was missing. I didn't like what came out. I stopped, took a break for a few months. When I returned to photography -- I was about twenty-one years old then -- I took one step back. I stopped trying to recreate, stage, things that happened, in a controlled way. Rather, I tried to do what I did when I first started: shoot things as they were happening. I began to work in color too which is, for me, warmer, more vivid. I gave no advance warning, required no cooperation, shot in quantity. Snapped, developed, looked at the results, and over again. For the most part it was still my mother and myself, but working intensively, and instinctively, everyone who was intertwined in our lives - my father, my brother Pinni, Eran, my grandparents, my cousins - all were drawn in. The frame became flexible and hospitable. Things I had previously considered marginal drifted to the center and often became themes in their own right. Ironically, the closer I got to the details, the more I zoomed in the more universal the themes turned out to be. Moving in turned out to be moving out. Work on minute details - a mark on the skin, a stitch, a hair, an eye, a kiss - carried the work beyond the boundaries of my family. The presence of the camera too became more familiar, more relaxed. Still, it generated, not just documented, situations. Not because it had a personality, but because it aroused an attitude. By the very fact of documenting, the image competed with its object, showed it in a different, yet not at all false, light. It's like facing a mirror: when you look into it, you tighten your face muscles slightly, change your expression. I found myself and my family discovering more about ourselves, or at least, discovering nuances we couldn't otherwise see. Sometimes, the photographs came before I could articulate what it was that triggered them, giving form to some unformed feeling. More than that, the camera sometimes dares say what I don't dare think. These lines, between what I thought I saw in life, what I saw in the photographs, what I thought I saw in the photographs, became confusing in many ways. Like a permanent double take, I was not always sure if something - a mood, a sigh, a frown - captured an actual event, or if I was imposing on my memory a fraction the camera had caught. It often feels like I have two, parallel sets of memory. And yet, as complicated as the relations between representation and life may be, I do trust the camera, and what it captured is, in many ways, real. The camera is, in fact, often less biased than my eyes. And since it preserves something from life - It would not otherwise be valuable for me - it is also a record. When I have something in a photograph, I feel like it is safe from time, I feel like I can also part with it. It gives me the illusion of having the actual past for safekeeping.