© Jules Spinatsch, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Luciano Fasciati, Chur, Christophe Guye Gallerie, Zürich

Jules Spinatsch »

Semiautomatic Photography 2003-2020

Exhibition: 12 Dec 2018 – 2 Feb 2019

Tue 11 Dec 18:00

CPG Centre de la Photographie Genève

Promenade des Bastions 8

1205 Genève

+41(0)22-3292835

cpg@centrephotogeneve.ch

www.centrephotogeneve.ch

renovation

© Jules Spinatsch, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Luciano Fasciati, Chur, Christophe Guye Gallerie, Zürich

Jules Spinatsch is one of the most important Swiss photographers on the international scene today. To be specific, he has exhibited at the MoMA in New York, the Fondation Cartier in Paris, the Villa Arson in Nice, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Tate Modern in London, the SFMoMA in San Francisco, as well as at Kunsthaus Zürich or the Fotomuseum Winterthur, to mention only those institutions.

The exhibition sums up the panoramic photography projects he has carried out between 2003 and 2018. The artist first used a webcam technique he had developed in collaboration with the engineer Reto Diethelm, then after 2012 he used a computer-controlled SLR that he programmed himself. To explain the principle in a few words: Following a precise grid, a camera records single images at regular intervals over a timespan of between one and 24 hours. Then all the single images are combined in chronological order into a large panoramic view. The panoramic image conveys one continuous space that is cut into time fragments. Once the camera is released, it runs on its own. The camera controls the space but not the action.

"Jules Spinatsch Semiautomatic Photography" is a continuous sequence of manual and automated image-making. Starting in 2003, the date of his first solo exhibition at the CPG entitled Temporary Discomfort, he succeeded in responding artistically to a method of photographic production which would subsequently only become more widespread, namely automated surveillance photography. The first panorama made in 2003 during the World Economic Forum [WEF] in Davos, the photographer’s birthplace, marks a turning-point in the history of critical documentary photography.

It has to be remembered that three years earlier Allan Sekula had immortalised the nascent alternative globalization movement in Waiting for Tear Gas. As a private citizen (with no press card or accreditation) he photographed the major demonstration in Seattle against the globalisation of the economy from within the middle of the crowd.

Jules Spinatsch installed three computer-controlled cameras in a library and two residential buildings near the Congress Center where the summit was being held, to record the area from three different angles: on the one hand the Congress Center’s accesses and the procession of alternative globalization demonstrators which, having been held up by the Black Blocs, arrived too late in relation to the camera’s programming, and therefore remained invisible. He was not in the crowd, but at a distance, with his programmer, shielded from the public gaze and the two groups expected to be confronting one another (the demonstrators and the police). The 2176 individual photographs were transmitted from Davos to Zurich, where the single images were mounted to form a 20-metre long panoramic view, constituted over the five days of the summit, in the art space Walcheturm.

As happened in Davos, one of the main qualities of Jules Spinatsch’ strategy is the contradiction between the programme’s schedule, and the actual course of the events that unfold in front of the automatic camera. This absurdity is also a quality of the work Heisenbergs Offside, which recorded the World Cup qualifying match between France and Switzerland in 2005, showing the entire Wankdorf stadium in Bern without ever showing the ball on the field.

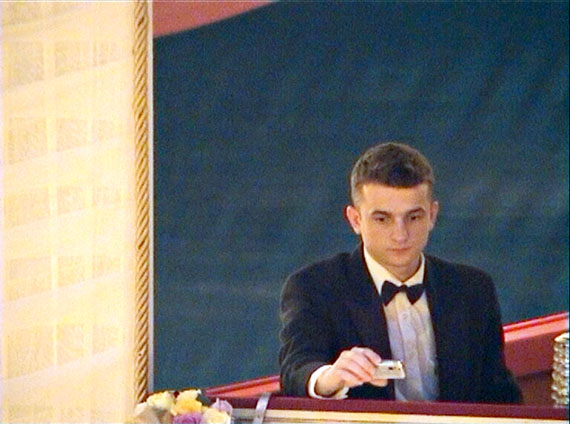

Two thirds of the semiautomatic projects depict places associated with power, whether judicial as in Panopticon JVA (a Mannheim prison), financial as in Competing Agendas (the Frankfurt Stock Exchange) or political as in Fabre n’est pas venu (Toulouse City Council offices), or places associated with leisure, such as Heisenbergs Offside or Vienna MMIX 10008/7000 (Vienna Opera House) or the Tanzboden 1 (a rave party in Mannheim). This assumed equivalence between sites of power and entertainment venues is directly inscribed in the logic of our mercantile societies that subjugate humanity in all spheres of life and in which free time is no more free than working time.

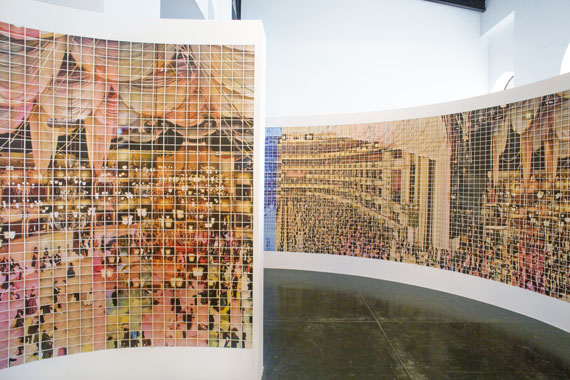

During recent years Jules Spinatsch has become increasingly interested in the independent qualities of single images: in particular the absence of intention in automated creation. On the one hand it leads to a new relationship between the author and his material, but it also impacts on the audience’s expectations of authorship. He treats the single images as an archive which leads to a variety of final forms, something he explored to the full extent in the Vienna work: a circular panorama installation, blocks of rearranged single images, then a two-volume book, that combines these two approaches. Finally for this exhibition he presents a video sequence of the recording at the time, one image every three seconds, in real time.

The Centre de la photographie Genève is staging a first comprehensive exhibition of Spinatsch’s semiautomatic photography projects. The exhibition is roughly structured into four parts :

The entry hall introduces the raw material – single images from various projects, presented as posters, detached from their original context. On the right-hand side, the ground floor is entirely occupied by the artist’s inaugural works from Temporary Discomfort, Chapter IV, including the installation as shown and acquired by MoMA (N.Y.) in 2006. Soft valley, a panoramic recording again from Davos 2003 and never previously released, is also shown. The left-hand side concentrates mainly on his latest projects: Inside SAP and Panopticon JVA, recordings at the headquarters of the multinational software corporation SAP and at a panoptical prison, both located in or near Mannheim. As a quintessence, they provide their own visual analysis, embedded in a functional analogy between the software and the prison industry.

The first floor displays a wide range of projects from 2005 to 2012, in a variety of final forms: framed panoramas, a unique spiral-shaped panorama Vienna MMIX – Cul de sac, an unseen view of a controversial Geneva urban structure in Snowdon Habitat. The installation relating to the history of nuclear technology, Asynchron I-III, and a new series, Sous la table – Fabre extracted from Fabre n’est pas venu, a panorama of Toulouse City Council, should also be mentioned.

Next to the exit of the CPG, the artist takes visitors into a photographic reconstruction of his own studio. After covering events and places of power and entertainment in public and semi-public spaces, the artist invites us into his private sphere.�

© Jules Spinatsch, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Luciano Fasciati, Chur, Christophe Guye Gallerie, Zürich

Jules Spinatsch zählt zu den wichtigsten Schweizer Fotokünstlern mit internationaler Bedeutung. Er hat in Institutionen wie dem MoMA New York, der Fondation Cartier in Paris, der Villa Arson in Nizza, dem Walker Art Center in Minneapolis ausgestellt, daneben in der Tate Modern in London, im Haus der Kunst in München, dem SFMoMA in San Francisco, im Kunsthaus Zürich und im Fotomuseum Winterthur. Vom Centre de la photographie Genève (CPG) wurde er schon 2003 und 2015 mit Einzelpräsentationen vorgestellt und seine Werke waren Bestandteil von weiteren vier Gruppenausstellungen. Die erste umfassende Bestandsaufnahme seiner halbautomatischen Arbeiten erfolgt nun ebenfalls in Genf.

Die Ausstellung präsentiert die umfangreiche Werkgruppe der Surveillance Panoramas, die der Künstler zwischen 2003 und 2018 geschaffen hat. Zunächst kam eine Webcam-Technik zum Einsatz, die er in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Ingenieur Reto Diethelm entwickelte. Nach 2012 begann er, eine computergesteuerte Spiegelreflexkamera entsprechend selbst zu programmieren. Das Prinzip ist einfach: In regelmäßigen Abständen hält die Kamera einem vorgegebenen Raster folgend nacheinander Einzelbilder fest – dabei werden über eine Zeitraum von einer bis zu 24 Stunden teils mehrere tausend Belichtungen registriert. Die Aufnahmen werden am Ende in chronologischer Reihenfolge zu einem großen Panoramabild zusammengerechnet, welches den Bildraum kontinuierlich wiedergibt, die Ereignisse aber, die innerhalb der Zeitdauer stattfanden, nur fragmentarisch und zufällig abbildet. Denn ist der Prozess einmal gestartet, läuft das Aufnahmeprogramm von alleine ab.

Die halbautomatische Fotografie von Jules Spinatsch ist eine fortlaufende Abfolge von manueller und automatisierter Bildherstellung. Seit seiner ersten Einzelausstellung im CPG 2003 mit dem Titel Temporary Discomfort gelang es ihm, künstlerisch auf eine fotografische Praxis zu reagieren, die sich später weit verbreitete, nämlich die automatisierte Überwachungsfotografie. Das erste Panorama, das 2003 während des World Economic Forum WEF in Davos, dem Geburtsort des Fotografen, generiert wurde, markiert einen Wendepunkt in der Geschichte der kritischen Dokumentarfotografie. Allan Sekula produzierte vier Jahre zuvor Waiting for Teargas, ein Karussell mit 81 Dias der ersten Alter-Globalisierungsdemonstration. Als Privatbürger (ohne Presseausweis oder Akkreditierung, ohne Teleobjektiv und Gasmakse) fotografierte er aus der Mitte des Demonstrationszuges in Seattle.

Während des WEF installierte Jules Spinatsch drei computergesteuerte Kameras in der Nähe des Kongresszentrums; eine an der Fassade einer Bibliothek und zwei in Wohngebäuden. Zwei überwachten die Zugänge zum Kongresszentrum, eine dritte den Demonstrationszug, der jedoch vom schwarzen Block aufgehalten wurde und so ist die Straße, über der ein Luftballon mit Werbung für die Financial Times schwebt, leer. Jules Spinatsch befand sich im Gegensatz zu Sekula nicht zwischen den Demonstranten, sondern fern von allen Blicken. Das Panorama B251356, zum ersten Mal im CPG als wandfüllende Tapete gezeigt, kündigt die Zukunft des WEFs an: inzwischen gibt es in Davos keine Demonstrationen von Globalisierungsgegnern mehr. Eine weitere Kamera übertrug während dem fünf Tage dauernden Gipfel 2176 Bilder von Davos nach Zürich direkt in den Kunstraum Walcheturm, wo daraus ein 20 Meter langes Panoramabild entstand.

Jules Spinatschs Strategie wohnt etwas Absurdes inne. Denn Zufall und Kontrolle sind zwei sich ausschließende Qualitäten. Die Arbeit Heisenbergs Offside führt diese Diskrepanz bestens vor: während dem WM-Qualifikationsspiel zwischen Frankreich und der Schweiz im Jahr 2005 ist zwar das gesamte Wankdorf-Stadion in Bern zu sehen und das bis in den hintersten Logenplatz, aber kein einziges Mal ist der Ball im Bild.

Zwei Drittel der halbautomatischen Projekte stellen Orte der Macht dar, sei es juristische Macht mit Panopticon JVA (einem Mannheimer Gefängnis), finanzielle Macht mit Competing Agendas (die Frankfurter Börse) oder politische mit Fabre n'est pas venu (der Sitzungssaal des Stadtrats von Toulouse). Der andere Drittel zeigt Freizeitorte wie mit Heisenbergs Offside oder Vienna MMIX 10008/7000 (Wiener Opernball) oder auch mit Tanzboden 1 (einer Rave-Party in Mannheim). Diese Gleichwertigkeit von Macht- und Unterhaltungs-Orten entspricht der Logik unserer Warengesellschaften. Die Ausbeutungskriterien sind die selben, sei es in der Arbeits- oder in der Freizeitwelt.

In den letzten Jahren hat sich Jules Spinatsch zunehmend für die eigenständige Qualität der Einzelbilder interessiert, insbesondere für das Fehlen von künstlerischen Absichten im automatisierten Prozess. Der Autor wird sich einer gewissen Entfremdung gegenüber seinem Material bewusst, aber auch Erwartungen des Publikums an Autorenschaft werden teilweise enttäuscht. Heute behandelt er die Panoramen wie ein Archiv, dessen Inhalt in verschiedenen Präsentationsformen münden kann. Die Arbeit über den Wiener Opernball dient als gutes Beispiel: zuerst zeigte er die mehr als 7000 Einzelbilder chronologisch geordnet als Rundpanorama-Installation im öffentlichen Raum, dann präsentierte er in einer kommerziellen Galerie mehrere Bild-Blöcke von neu arrangierten Einzelbildern, anschliessend gibt er in einem Foto- und Architekturverlag ein 2-bändiges Buch heraus, mit sämtlichen Einzelbildern. Jetzt für die Ausstellung im CPG werden die Bücher zerschnitten und jede Seite wird chronologisch fortschreitend auf die Wand einer Spirale geklebt. Und zusätzlich zeigt er in der aktuellen Retrospektive eine Videosequenz in Echtzeit der Aufnahme: alle drei Sekunden ein Bild.

Die Ausstellung im Centre de la photographie Genève ist in vier Teile gegliedert: Der Eingangsbereich stellt das Rohmaterial vor: Einzelbilder aus verschiedenen Projekten, die als Poster gezeigt werden, losgelöst vom ursprünglichen Kontext. Die rechte Seite des Erdgeschosses ist fast vollständig mit Arbeiten aus Temporary Discomfort Chapter IV, einschließlich der 2006 vom MoMA (NY) gezeigten und erworbenen Installation, bestückt. Weiter wird Soft Valley gezeigt, eine noch nie veröffentlichte Panorama Aufnahme von Davos, ebenfalls aus dem Jahr 2003.

Im linken Teil des Erdgeschosses werden die neuesten Projekte vorgestellt: Inside SAP und Panopticon JVA - Aufnahmen aus dem Hauptquartier des multinationalen Softwarekonzerns SAP und aus einem panoptischen Gefängnis, beide in Mannheim realisiert. Der Software-Hersteller u.a. für Gesichtserkennungsprogramme und das Gefängnis sind auf dem selben Grundriss gebaut: ähnlich jenem Panoptikum, wie es Jeremy Bentham im 18. Jahrhundert für eine Gefängnisreform entworfen hatte und wie es von Michel Foucault als Metapher für unsere Kontrollgesellschaften wieder aufgegriffen.

Im ersten Stock ist eine breite Palette von Projekten aus der Zeitspanne 2005 bis 2012 in unterschiedlichen Formen zu sehen: gerahmte Panoramen, das einzigartige spiralförmige Panorama Vienna MMIX – Cul de sac, ein unbekannter Blick auf die größte und umstrittenste Genfer Überbauung in Snowdon Habitat. Die Installation Asynchron I–III rollt die Geschichte der Kerntechnologie in der Schweiz auf und außerdem stellt der Künstler eine neue Lesart von Fabre n'est pas venu vor: Sous la table – Fabre, eine Bildserie aus dem Panorama des Toulouser Stadtparlaments.

Ganz am Ende gewährt Jules Spinatsch den Besuchern noch Einblick in seine Privatsphäre und präsentiert die fotografische Rekonstruktion seines eigenen Ateliers.�

© Jules Spinatsch, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Luciano Fasciati, Chur & Christophe Guye Gallerie, Zürich

Museum of Modern Art, New York, in "New Photography 2006"

© Jules Spinatsch, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Luciano Fasciati, Chur & Christophe Guye Gallerie, Zürich

Panorama Recording, Operahouse Zurich, 2012

© Jules Spinatsch, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Luciano Fasciati, Chur & Christophe Guye Gallerie, Zürich