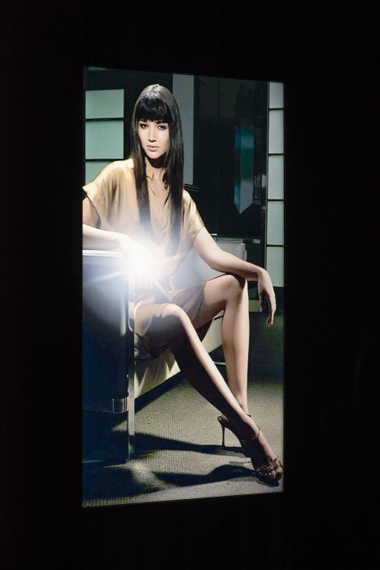

Video, 3D-Animation. 16:32 Min

Image courtesy of the artist and Tallinn Art Hall

Marge Monko »

Diamonds Against Stones, Stones Against Diamonds

Exhibition: 12 Jan – 11 Feb 2018

Tallinn Art Hall

Vabaduse väljak 6

10146 Tallinn

+372-6-6442818

info@kunstihoone.ee

www.kunstihoone.ee

Wed-Sun 12-19

Stones Against Diamonds, Diamonds Against Stones

Evelien Bracke

My passion for stones continued to grow. By the age of 15 my new love was a window display on the Via Condotti, which was always full of antique jewels. At least once a week, on the way home from my school on Via Ripetta, I’d stop and gaze at the display.

Lina Bo Bardi (1947)

In the essay Stones Against Diamonds from 1947, architect and designer Lina Bo Bardi describes her fascinated preference for semi-precious stones over gold, pearls and diamonds. Her first favourite is a little blue labradorite – the same stone that urged sociologist Roger Caillois, that other famous stone lover, to start his collection and to publish his book The Writing of Stones in 1970.

Until the late forties, diamonds were regarded as colourless, compared to more exotic stones like rubies or sapphires. Historically connected to danger, war and poison, they weren’t considered as tokens of love. The change of the valuable meaning of the gems into synonyms of love can be traced back to an ingenious marketing strategy by international diamond company De Beers. In the same year that Lina Bo Bardi wrote Stones Against Diamonds, De Beers started promoting diamonds against stones by launching its iconic campaign: ‘A Diamond is Forever’. The slogan, created by New York advertisement agency N.W. Ayers, perfectly captured the sentiment De Beers was aiming for: a diamond, like a relationship, is eternal. People were discouraged from reselling their diamonds, since this would disrupt the market and reveal the low intrinsic value of the stones. De Beers created and manipulated demand for diamonds by monopolising the market, changing social attitudes and convincing people that a marriage isn't complete without a diamond ring.

In her latest video and installations, Marge Monko takes this remarkable approach by De Beers as a case study to explore the phenomenon of desire and the codes and strategies that are used to present consumer goods. In the artistic practice of Monko, trained as a photographer, the analysis and impact of visual media is a recurring topic. In a world where practices as diverse as operative surgery, legal decision-making and even warfare are largely image- based, insight into the mechanics behind visual representation is indispensable. Although we are constantly surrounded by images, this regular engagement does not necessarily make us visually literate. Most of the time, we are not aware of the tools and codes used in advertisements to create a seductive narrative for a product. Advertising is an important and clever mechanism that helps brands establish the association of physical and social ideas with consumer goods.

De Beers for example succeeded in linking diamonds with emotions. It was the perfect artificial connection, because love and marriage were socially valuable and eternal. The diamond engagement ring, as we all know it, was an invention of De Beers. It was also a new kind of product, reinventing the idea of diamonds as necessities, rather than temptations or frivolities, and unloading these diamonds on the biggest new market in the world. The smallest, least desirable stones were dressed up as special and important.

Monko collected advertisements by De Beers from the 1950s to the present to study the construction of desire and the representation of women through images. In particular, the ‘Women of the World, Raise your Right Hand’ campaign from 2003 attracted her attention. The campaign targeted women with enough money to buy a diamond ring, using slogans such as “Your left hand rocks the cradle. Your right hand rules the world”. It was a clever way to evolve, and to promote non-engagement rings with diamonds for a growing target group. The terms ‘right hand ring’ or ‘power ring’ are relatively new, but the idea of wearing a ring on the right hand to show a woman’s economic independence has its roots in the original cocktail rings of the 1920s. As prohibition swept across America, women partaking in the underground drinking scene wore brightly coloured, oversized rings, purchased with their own money. Women enjoyed more freedom and spending power. The

glamorous Art Deco jewellery reflected this new-found consumerism. De Beers has continuously searched for new target groups, such as men and married couples celebrating their love. Time and again, the company reinvents itself.

Monko has also studied the architecture of shop windows, especially those of jewellery stores. What are the forms and codes that create consumer desire and communicate exclusiveness? In an age conducted by the economy of attention, shop windows are the public playgrounds of capitalist temptation. Seductive strategies of acquisition utilise displays as agents between the outside and the inside, suggesting the latter as promising spaces of illusion, fulfilment and satisfaction. But displays perform the connection between inside and outside the other way round as well: beyond the temples of consumerism they are capable of bringing the inside out, providing a platform for public interventions. The display implies an alternative exhibition format for artists and cultural institutions; the public audience is involved in a dialogue. This double concept of the display is also at play in Tallinn City Gallery, with its large windows facing two fashion boutiques on the opposite side of the street. Monko activates these ideas by placing an extra display cabinet in the front space of the City Gallery and by treating the windows of the space as shop windows that blend in with the shops in the street. The result is an attractive but critical attitude towards the visual media that determine our experience of the world.�