épreuve au gélatino-bromure d'argent

© Collection Crispini, Genève

Montagne Magique Mystique

Treasures of Photography from Swiss Collections

Exhibition: 8 May – 26 Sep 2021

MBAL Musée des beaux-arts

Marie-Anne-Calame 6

2400 Le Locle

+41 (0)32-9338950

Wed-Sun 11-17

© Albert Nyfeler, Médiathèque Valais – Martigny

"Montagne Magique Mystique"

Treasures of Photography from Swiss Collections

Exhibition: 7 May – 26 September 2021

Photography, born in the 19th century, accompanied the discovery of the mountains. The year following its invention, the first photographers set up their darkrooms in the middle of the Alpine landscape. Most of them were enlightened amateurs, passionate about the new medium, which offered images of extraordinary precision. To record and fix the image from the action of light, a good knowledge of chemistry and physics was required. The first photographic process, developed in 1839 and called the daguerreotype, dominated the market until 1850. Requiring long exposure times and producing a single image, the daguerreotype is a photograph on a thin copper plate coated with silver. Although only a handful of daguerreotypes of the Alps were produced in the 1840s, mostly at medium altitudes, and even fewer survive, some images were reproduced in albums as engravings and lithographs. Throughout the 19th century, photographers made numerous technical improvements to the process, notably moving from the single metal plate of the daguerreotype to the negative,

which allowed images to be produced on paper in large quantities.

The various stages of development were also gradually simplified, and exposure times reduced. The metal plates were replaced by glass plates, covered with a layer of photographic emulsion, and then developed in a chemical bath. With the invention of the negative-positive process, photography became reproducible: the image produced on the glass plate was then printed on photosensitive paper, known as albumen.

From the mid-19th century onwards, it was possible to produce unlimited numbers of prints. This led to a boom in the photographic market and publishers specialised in photographic views, distributing their images in albums which they sold to sold to a curious public at home and abroad. Faster and cheaper than in its early days, photography became accessible to the greatest number of people and was eventually taken on all journeys.

As the profession of photography developed in the 1850s, particularly as a result of the craze for photographic portraiture, many amateurs with the means to buy equipment learned to master the new medium. Among the first photographers were artists who saw it as a quick and efficient way to develop images, but also doctors, engineers and pharmacists with a penchant for science who were fascinated by the medium. From the late 1840s onwards, photographic equipment was taken on excursions: mountaineers in particular saw it as a way of sharing their passion for the mountains. As for professional photographers, they were integrated into the scientific missions of discovery of new territories, and brought back to the public unpublished images of the exploration of the high peaks. It isn’t barely an exaggeration to say that the Alps were invaded by photographers in the decades following the invention of the process.

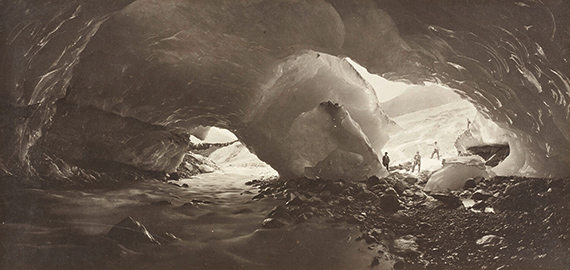

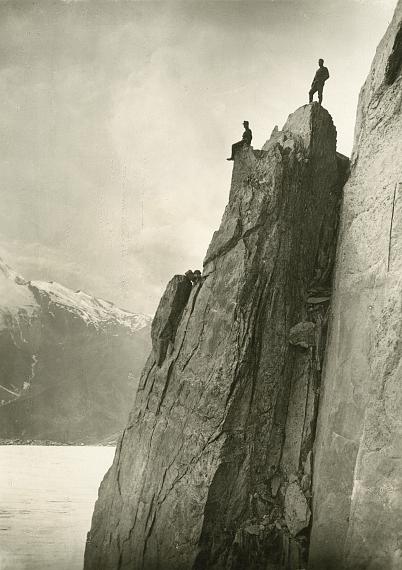

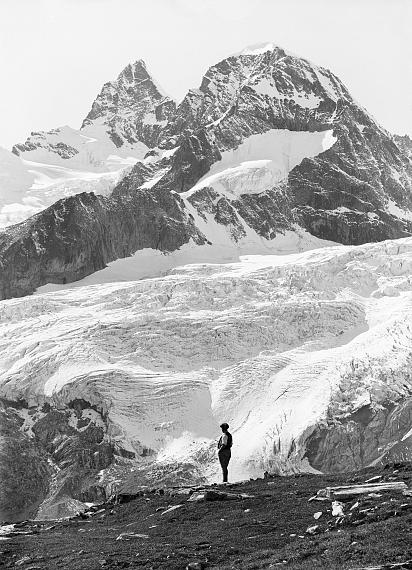

Although they struggled with difficult conditions, working with cumbersome equipment that in the early years required them to carry chemicals, glass plates and darkroom tents along cliffs, photographers managed to produce extraordinary images, offering a variety of viewpoints, sometimes offering panoramic views, sometimes focusing on seracs, glacial caves, gorges and waterfalls. But not all the photographers set out to conquer the high peaks. Some stayed at mid-altitude

and photographed the mountain people, their habitats and their way of life. Geologists photographed rock formations and ice seas, beginning to document glacial movements scientifically, while civil engineers were interested in the infrastructure that opened up new routes through the mountains, such as the railway.

The exhibition shows the enthusiasm of the first generations of photographers for mountain landscapes in particular. Corresponding to the first 100 years of the history of photography, the period 1840-1940 shows the fundamental change in attitude towards the high peaks: this wild and dangerous space is suddenly perceived as a place of glorious nature and great beauty. The air is pure compared to the dark and unhealthy environment that develops in the cities. People went to the mountains for treatment and to distance themselves from the hustle and bustle of the city. Sanatoriums were founded in Switzerland at the end of the 19th century. Altitude cures were prescribed to patients who were recommended to engage in outdoor activities and to expose themselves to the sun. Thus, the mountains were symbolically associated with the health of the body, which in turn was associated with spiritual health. This period also coincides with the golden age of mountaineering, when all the great peaks were climbed. Explorations were adventurous not only in the Alps, which in the 19th century were still a territory to be discovered, but also on all other continents, from Africa to the Arctic, from New Zealand to the Andes, from Alaska to Tibet.

© Courtesy Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

Climbing became an expression of male virility: the mountains had to be "conquered". It was then that specialised alpine clubs were born: the first was founded in England in 1857, the Swiss Alpine Club was born 6 years later. Once the challenge of conquering the Alps was over, the focus shifted to Everest and K2, nicknamed the "wild mountain" because of the difficulty of its ascent. Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, a doctor from Neuchâtel, was one of the first to attempt to climb the world's second highest peak in 1902. He brought back many pictures.

Finally, it was also in the late 19th Century that tourism developed with all its infrastructure: roads and railways, with their bridges and tunnels, steamships, hotels and related tourist services. Photographic imagery accompanied this development, as did mountaineering: stereoscopic views (the forerunner of 3D) became wildly popular, with millions of copies sold, while the first photographic postcards appeared in 1870, allowing people to travel vicariously through the

image. In the space of a few decades, photography became central to all human activities, whether commercial, documentary, scientific or artistic. Hundreds of thousands of mountain photographs were taken between 1840 and 1940: the trickle rapidly became an avalanche, and many of those images were then reproduced in great numbers. While many originals have disappeared over time, thousands of prints have survived in various collections. Not surprisingly, the Swiss in particular have a penchant for such images. However, the passion is widely shared beyond our borders—as a place representing the sublime, or merely the picturesque, the mountains offer myriad possibilities for aesthetic exploration by photographers, who have learned over the decades to deftly capture the nuances of bright light and deep shadow. The technical limitations (the image in black and white and not in colour, the large format negatives requiring technical know-how) are quickly diverted to the benefit of a strong aesthetic.

In this respect, the approach to landscape photography by the American Ansel Adams is still being emulated in the digital age. Mountain photography has become a genre in itself—though its parameters are somewhat blurred—not only because of the aesthetic pleasures it allows, but also because of what it represents: a natural realm to be protected, while remaining a territory to be tamed and exploited. These diverse and contradictory approaches are at the heart of 'mountain photography', suggesting an aesthetic and moral issue that combines physical hardship and suffering while offering a sense of identity and space for contemplation. What characterises early mountain photography is an eminently photographic work on the territory and the limit. And it is certain that in the 21st century the genre has lost none of its powers of concentration.

Curators:

William A. Ewing with Nathalie Herschdorfer

Focusing on the first 100 years of the history of photography, the MBAL's research reveals more than 200 photographs, many of which have never been shown to the public. To produce this exhibition, the museum collaborated with 18 Swiss public and private collections.

Bibliothèque de la Ville de la Chaux-de-Fonds

Bibliothèque nationale suisse, Berne

Collection Daniel Schwartz

Collection Doy Young et Gaudenz F. Domenig

Collection Nicolas Crispini

Collection Richard de Tscharner

Collection Thomas Walther

Fondation Auer Ory pour la photographie, Hermance

Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

Médiathèque Valais – Martigny

Musée Alpin Suisse, Berne

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Neuchâtel

Musée des beaux-arts, Le Locle

Musée gruérien, Bulle

Musée national suisse, Zurich

Musée suisse de l’appareil photographique, Vevey

Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana, Lugano

Zentralbibliothek, Soleure

The exhibition was supported by the Fondation Le Cèdre, the Fondation Philanthropique Famille Sandoz and the Contrôle des

Métaux Précieux.

© Emile Gos, Médiathèque Valais – Martigny