LIU Zheng »

Revolution

Exhibition: 25 Apr – 13 Jun 2004

798 Photo Gallery

4 Jiuxianqiao, Chaoyang District

100015 Beijing

+86-10-64381784

798@798photogallery.cn

www.798photogallery.cn

Daily 11-18

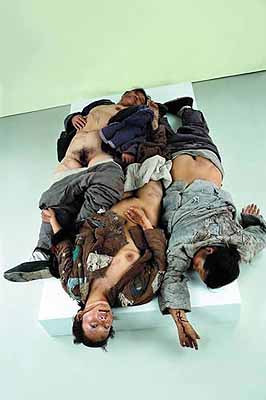

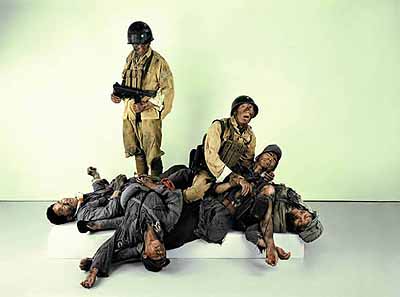

In his new art series – Revolution, Liu Zheng expresses his pioneering intention through innovative historicism. "Bid farewell to revolution", through the medium of photography and retrospect revision, reveals the disregard of humanness during revolution and war and the accompanying distortion and deceit of recorded history. The memories of history brought by his large surrealistic pictures are no less shocking than that of Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. The absurdity and alienation produced by the dramatic and eerie effects of the pictures are true to the original state of history. But, there is one point we can’t evade – the epic of revolutionary heroism is completely rewritten by a series of photographic poetics of existentialism. Death, massacre, violence and sexual desire are the main subjects of the unofficial history revealed in a stimulating and/or surreal visual of postmodernism, which makes it difficult to differentiate between the false and the true -- the real and the sham. Liu Zheng’s concept of photography contains negative overtones. To him, historical existence per se has no true authority. The subject matter is merely a hypothetical proposition and, as such has no inherent credibility. Each of the hypothesized events has to defend itself in light of the individual viewer’s assessment. In fact, positivistic photography holds the "objective fact" in such high esteem that it attempts to force idealism into a synthetic historical pattern and passively follows the ideal of social existence. Therefore, it neglects and denies the negativity of accurate historical development, ignoring emotional nuance and, instead, employs imaginative vitality and the essence of fabrication–things that photography, as an art form, should address. Liu Zheng eventually derives his approach to photography from August Sander’s social documentary. In Liu’s earlier works, like the series of Chinese Men, we can see the delicate mode of positivism adopted by August Sander’s Men of the 20th Century. Liu’s work has turned the mode into a theory. However, Liu’s positivism always includes elements of the misery and confusion of belief and hints of hidden bitterness and indignation of idealism. How could August Sander make his photographic objects cast away their self-conscious vanity and face his lens directly? Why, in a historical manner, do his subjects always tell us that we did look like this at that moment? This is an unanswered question in the history of photography. What is worth our discussion is how Liu Zheng decoded the faults of August Sander’s social documentary and transferred those faults into dual inner-driven forces - negativity and decisiveness. Firstly, after he finished the series of Chinese Men, Liu Zheng no longer takes instant reality and precise details as the intrinsic proposition of photography. Rather, he uses them to expand and give freedom in ways that can better express the adaptation of concepts. In this manner he realizes that the fabrication, action and simulation of history are reliable ways for photography to interpose history. Thus, the traditional significance of history or "revolution" is suspended and the arena of descriptiveness can be probed vigorously and boldly. Secondly, by combining the artistic techniques of film, drama, sculpture and make-up, he pushes the potential and future of directed photography to the limits of revolutionary historical narration. The goal is to build an image of the ripple effects of history by connecting the elements of the pictures. This will develop the analytical abilities of the audience and they will be aroused to imagine, question and doubt pictures from many different aspects. From the aforementioned objectives we can see Liu Zheng adopts the spirit of modern rationalism and an imaginative, cognitive approach in sociology and anthropology from August Sander’s philosophy of photography aesthetics. Later he also integrated ideas from Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall’s postmodern photography concepts. Liu’s difference lies in his concern and thought regarding the relationship of the Chinese people’s historical plight and reality, as well as his concern of the dilemma faced by the innocent common masses. The process of the conception of Revolution is in fact the reappearance of the memory of revolutionary history. Its difficulty lies in how to approach the prototype of historical memory. To those who were born after the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), memories of the "revolution" come from reading, text and pictures-it is a kind of taught and trained memory. Therefore, Liu Zheng tries to restore the many faces of history by retrieving his own array of memory channels. He frequents waxwork museums and is intrigued by the surreal images of the wax figures. At the same time, he is depressed by the grotesque strangeness of the wax figures. From this experience, he derives the basic image of "revolution." However, the result of "revolution" is a factual, social reality. Hence, unbounded realism and new historicism are two bitter gourds growing on the same vine. Apparently, the image of Revolution is the "historical fact" recorded by instant photography. However, now is the time for organization and action and most certainly not the time to rest on historical or artistic laurels. By setting people’s minds on just goals, a new pattern of legitimate history can be realized. What we will realize in the make-up, acting, repeated postings and photographs is the unblemished truth in the critical, considered evaluation of people’s consciousness-that is THE desired reality. The image of Revolution generates a network through time and space that exists never/forever/whenever. The more outstanding a photographic work is, the more marvelous, comprehensive and moving the creativity as it lives in a fabric of space and time. In a post- revolution atmosphere people should dynamically increase their mental faculties to include an omni-directional cognitive system and not be satisfied with a common mono-directional knowledge of history. Only in this manner can REVOLUTION and revolution have a significant differentiation and affect our lives in personal, cultural and political opinions or in dramatic, common or historical analyses. - Dao Zi