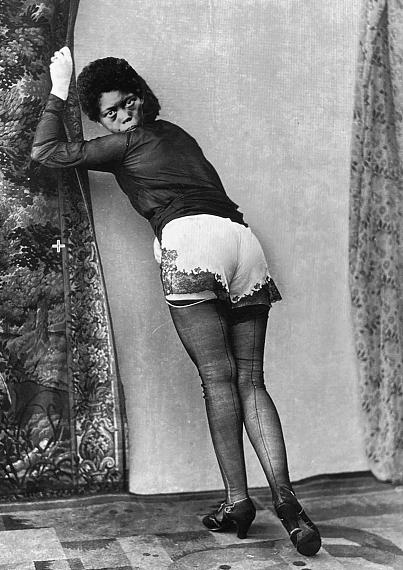

Turning, 2021

© Frida Orupabo and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin, Stockholm, Mexico City

Frida Orupabo »

I have seen a million pictures of my face and still I have no idea

Exhibition: 26 Feb – 29 May 2022

Fri 25 Feb 18:00 - 21:00

Fotomuseum Winterthur

Grüzenstr. 44+45

8400 Winterthur

+41 (0)52-2341060

info@fotomuseum.ch

www.fotomuseum.ch

Tue, Thu, Fri 11-17; Wed 11-20; Sat-Sun 11-18

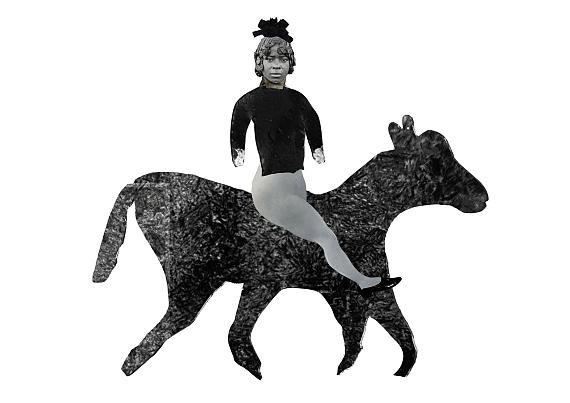

Girl on Horse, 2021

© Frida Orupabo and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin, Stockholm, Mexico City

Frida Orupabo

"I have seen a million pictures of my face and still I have no idea"

Exhibition: 26 February – 29 May 2022

Norwegian Nigerian artist and sociologist Frida Orupabo (*1986) creates analogue and digital black-and-white collages and video installations from visual material circulating online. From photographs from the colonial era as well as from contemporary imagery, from ethnography, medicine and science to art and pop culture, Orupabo dissects representations of the Black, mostly female body as a means to negotiate themes of colonial violence, racism, sexuality, identity and belonging. In rearranging and newly reassembling the dissected fragments, Orupabo creates figures of resistance that challenge how and what we see in a present-day reality that remains permeated by colonialism.

Orupabo’s exploration of personal and cultural belonging is the starting point for her delicate, sculptural collages and video works. In order to write herself into the (hi)stories that leave Black women invisible or twist the images she cannot recognise herself in, Orupabo dismembers images of Black bodies before reassembling them layer by layer. Processes of objectification, fixation and ‘othering’ are deconstructed, exposing, in a discomforting and disturbing way, how photography significantly contributes to the formation and perpetuation of colonial power relations and violence.

'I am interested in what we see and how we see. I engage with images from colonial archives and with collage as a medium to explore what they can do in terms of breaking things up, recreating and questioning.'

Frida Orupabo

Orupabo started posting on the social media platform Instagram, on which the nine-part video installation shown in the exhibition is based, nearly a decade ago. Using it as an ordering system, a form of expression and a personal archive, she also ventured with her work into a public arena for the first time. Orupabo arranges and condenses snippets of photographs, videos and text from a wide range of online sources into multi-layered narratives that seek to liberate the depiction of Black lives from one-dimensional representations and attribute to them instead the complexity, ambivalence and contradictions that form part of every human existence.

'I wish to create subjects that look back and question rather than being mere objects, a distant other that can be described and boxed in.'

Frida Orupabo

Orupabo’s collages are pervaded by subtly resistant and emancipatory moments: the direct gaze or the clenched fist; figures that fly or remain in a graceful, suspended state. They express pride and dignity as they attempt to transform the confining categories of image and imagination that they demonstrate or evoke.

The collage Batwoman exemplifies this dynamic by defying the racist gaze that looks down on Black people as if they were animals with a mixture of unwavering strength and graceful ease. Orupabo has not removed or retouched the logo of a picture agency which remains visible in the watermark on the photograph but instead appropriated it. Even when images from colonial archives circulate freely on the internet, the image rights are owned by primarily white institutions – which means that they not only financially benefit from these images but also have a say in the context in which they may appear. The collage furthermore reads as an ironic take on the superhero, a role usually reserved for men. Batwoman cares little for male fantasies. Instead of squeezing herself into a skin-tight bodysuit, she flutters away with her bat-like body, free from any sexist expectations. The collages presented at Fotomuseum Winterthur are an expression of Orupabo’s aesthetic exploration that attempts to escape the voyeuristic, sexualising and sexist gaze by rendering the gender of the collaged bodies increasingly indefinable. Finally, Orupabo expands her visual language by including motifs from Renaissance paintings as well as references to figurative painting.

In Orupabo’s collages, the fractures stand out visibly, like scars. They mark the violent, spatially and temporally dissociated colonial experience whose legacy continues to shape the everyday realities, life experiences and images of today. By appropriating the colonial visual memory, by tearing it apart, reassembling and rewriting it to narrate different potential (hi)stories, the scars also visualise the process of emotional labour. Perhaps they imply the possibility of healing – if we accept the challenge of the gaze, confront its moments of irritation and ambivalence, and become aware of its complex legacy and ways in which it operates.

Fotomuseum Winterthur presents the first solo exhibition of Frida Orupabo in Switzerland. As part of the accompanying programme, the artist Legion Seven will develop a sound performance that enters into a dialogue with Orupabo's works to explore the tensions of identity, belonging and representation. Legion Seven breaks with normative constraints: the wreckage of the literal cult rigidity into which they were born is scattered into dream mythologies, science fiction and chaos logics that spawn projects as diverse as the imagination. Conceived in collaboration with Museum Rietberg and its exhibition ‘The Future is Blinking’ (18.03.–03.07.2022), the newly developed performance will also address the tension that opens up between the two exhibitions in the way they speak of photographic representation and self-determination. The performance will take place on Wednesday, 18.05.2022, in the rooms of Fotomuseum Winterthur and on Thursday, 19.05.2022, in the rooms of Museum Rietberg.

Frida Orupabo (b. 1986) lives and works in Oslo, Norway. After studying sociology, she worked as a social worker with sex workers and victims of forced prostitution. Since 2013, Orupabo has been publishing her work on Instagram under the name @nemiepeba and since 2017 she has been exhibiting as an artist. Her work has been included in solo and group exhibitions internationally, including the São Paulo Art Biennial (2021), Kunsthall Trondheim (2021), Museum Ludwig, Cologne (2020), Venice Biennale (2019), Julia Stoschek Collection, Berlin (2018) and Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm (2018).

Closed Fists, 2021

© Frida Orupabo and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin, Stockholm, Mexico City

Frida Orupabo

"I have seen a million pictures of my face and still I have no idea"

Ausstellung: 26. Februar bis 29. Mai 2022

Die norwegisch-nigerianische Künstlerin und Soziologin Frida Orupabo (*1986) kreiert aus online zirkulierendem Bildmaterial analoge und digitale Schwarz-Weiss-Collagen und Videoarbeiten. Aus historischen Fotografien der Kolonialzeit sowie Bildern der Gegenwart, aus Ethnografie, Medizin und Wissenschaft sowie der Kunst und Popkultur seziert Orupabo Darstellungen des Schwarzen, meist weiblichen Körpers, um Themen wie koloniale Gewalt, Rassismus, Sexualität, Identität und Zugehörigkeit zu verhandeln. Im Neu-Arrangieren und Zusammenfügen zergliederter Bildfragmente entstehen widerständige Figuren der vom Kolonialismus geprägten Gegenwart, die uns zum Blickaustausch herausfordern.

Orupabos Auseinandersetzung mit persönlicher und kultureller Zugehörigkeit bildet die Ausgangslage ihrer feingliedrigen, skulptural wirkenden Collagen und Videoinstallation.

Schicht für Schicht setzt die Künstlerin zerschnittene Abbildungen Schwarzer Körper neu zusammen, um sich selbst in die Geschichte(n) einzuschreiben, die keinen Platz für sie vorgesehen haben, oder aber um die Bilder, in die sie hineingezwängt wird, so zu verdrehen, dass sie sich darin wiedererkennt. Prozesse der Objektivierung, Fixierung und Fremdbestimmung werden somit dekonstruiert, wodurch auf unbehagliche und verstörende Weise spürbar wird, wie die Fotografie massgeblich an der Bildung und Fortschreibung von kolonialen Machtverhältnissen und Gewalt beteiligt ist.

«Ich interessiere mich dafür, was wir sehen und wie wir sehen. Meine Beschäftigung mit Bildern aus dem kolonialen Archiv und der Collage als Medium untersucht deren Vermögen, Dinge aufzubrechen, zu zerlegen und in neue Zusammenhänge zu stellen.»

Frida Orupabo

Die Social-Media-Plattform Instagram, an die sich eine in der Ausstellung gezeigte Videoinstallation in ihrer neunteiligen Anordnung anlehnt, begann Orupabo vor ungefähr zehn Jahren als Ordnungssystem, Ausdrucksform und als persönliches Archiv zu nutzen. Gleichzeitig wagte sie sich über Instagram auch erstmals mit ihrer Arbeit an eine Öffentlichkeit. Orupabo arrangiert und verdichtet im Netz gesammelte Foto-, Video- und Textschnipsel aus unterschiedlichsten Quellen zu vielschichtigen Erzählungen, wobei sie die Darstellung Schwarzen Lebens aus eindimensionalen Repräsentationen herauslöst und ihm die Komplexität, Ambivalenz und Widersprüchlichkeit einer jeden menschlichen Existenz zugesteht.

«Ich möchte Subjekte hervorbringen, die auf die Vergangenheit blicken und diese hinterfragen, anstatt blosse Objekte zu sein, ein fernes Anderes, das beschrieben und in eine Schublade gesteckt werden kann.»

Frida Orupabo

Subtil widerständige oder emanzipatorische Momente durchziehen Orupabos Collagen: der direkte Blick oder die geballte Faust; Figuren, die fliegen oder in einem anmutigen Schwebezustand verharren. Sie strahlen Stolz und Würde aus und versuchen, jene eingrenzenden Bild- und Vorstellungskategorien zu transformieren, die sie zugleich vorführen oder zumindest andeuten.

Die Collage Batwoman bringt diese Dynamik beispielhaft zum Ausdruck, indem sie dem rassistischen Blick, der auf Schwarze Menschen herabschaut, als wären sie Tiere, mit einer Mischung aus unerschütterlicher Stärke und graziöser Leichtigkeit die Stirn bietet. Das Logo einer Bildagentur – als Wasserzeichen auf der Fotografie sichtbar – hat Orupabo nicht entfernt oder retouchiert, sondern sich ebenfalls angeeignet. Selbst wenn Bilder aus kolonialen Archiven frei im Netz zirkulieren, besitzen vornehmlich weisse Institutionen die Rechte – wodurch sie sich nicht nur an den Bildern bereichern, sondern auch über den Kontext mitentscheiden, in dem diese erscheinen dürfen. Gleichsam ironisch bricht Orupabo auch mit der Rolle des Superhelden, die in der Regel Männern vorbehalten bleibt. Dabei schert sich die Batwoman reichlich wenig um die Männerfantasien. Statt sich in einen hautengen Body zu zwängen, flattert sie befreit von sexistischen Erwartungen mit ihrem Fledermauskörper davon.

So sind die im Fotomuseum Winterthur präsentierten Collagen auch Ausdruck einer ästhetischen Suchbewegung Orupabos, die sich dem voyeuristischen, sexualisierenden wie sexistischen Blick zu entziehen versucht, indem das Geschlecht der collagierten Körper zunehmend undefinierbar wird. Schliesslich weitet Orupabo ihre Bildsprache auch über Motive aus Renaissance-Gemälden und Verweise auf die figurative Malerei aus.

In Orupabos Collagen treten die Bruchstellen sichtbar hervor wie Narben. Sie markieren die gewaltsame, räumlich wie zeitlich dissoziierte koloniale Erfahrung, die sich in den Lebensrealitäten, Erfahrungswelten und Bildern unserer Gegenwart fortschreibt. Indem sich Orupabo das koloniale Bildgedächtnis aneignet, es auseinanderreisst, neu zusammenfügt und daraus (eine) potenziell andere Geschichte(n) formuliert, sind diese Narben Ausdruck eines Verarbeitungsprozesses. Sie implizieren vielleicht aber auch die Möglichkeit einer Heilung – wenn wir uns auf die Blickbegegnung einlassen, uns ihren Irritationsmomenten und Ambivalenzen stellen und uns ihrer komplexen Wirkungsweise bewusst werden.

Das Fotomuseum Winterthur präsentiert die erste Einzelausstellung von Frida Orupabo in der Schweiz. Begleitend zur Ausstellung entwickelt Legion Seven eine Sound-Performance, die mit den Arbeiten Orupabos in einen Dialog tritt und das Spannungsfeld von Identität, Zugehörigkeit und Repräsentation erkundet. Legion Seven bricht mit normativen Zwängen: Die Trümmer der Kult-Starrheit, in die Seven hineingeboren wurde, werden in Traum- Mythologien, Science-Fiction und Chaos-Logiken zerstreut. Dabei entstehen Projekte, die so vielfältig sind wie die Vorstellungskraft. Als Kooperation mit dem Museum Rietberg und der dortigen Ausstellung «The Future is Blinking» (18.03.–03.07.2022) angelegt, arbeitet sich die neu entwickelte Performance auch am Spannungsfeld ab, das sich zwischen beiden Ausstellungen in Bezug auf Fragen zu fotografischer Repräsentation und Selbstbestimmung eröffnet. Die Performance findet am Mittwoch, 18.05.2022, in den Räumen des Fotomuseum Winterthur und am Donnerstag, 19.05.2022, in den Räumen des Museum Rietberg statt.

Frida Orupabo (*1986) lebt und arbeitet in Oslo, Norwegen. Nach ihrem Studium der Soziologie arbeitete sie als Sozialarbeiterin mit Sexarbeiterinnen und Opfern von Zwangsprostitution. Seit 2013 macht Orupabo ihre Arbeiten auf Instagram unter dem Namen @nemiepeba öffentlich und seit 2017 stellt sie als Künstlerin aus. Ihre Arbeiten waren international in Einzel- und Gruppenausstellungen vertreten, u.a. an der Biennale von São Paulo (2021), in der Kunsthall Trondheim (2021), im Museum Ludwig, Köln (2020), der Biennale di Venezia (2019), der Julia Stoschek Collection, Berlin (2018) oder der Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm (2018).

Batwoman, 2021

© Frida Orupabo and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin, Stockholm, Mexico City

Seated With Two Hands and Girl With Necklace, 2021

© Frida Orupabo and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin, Stockholm, Mexico City

Installation photo Kunsthall Trondheim: Susann Jamtøy