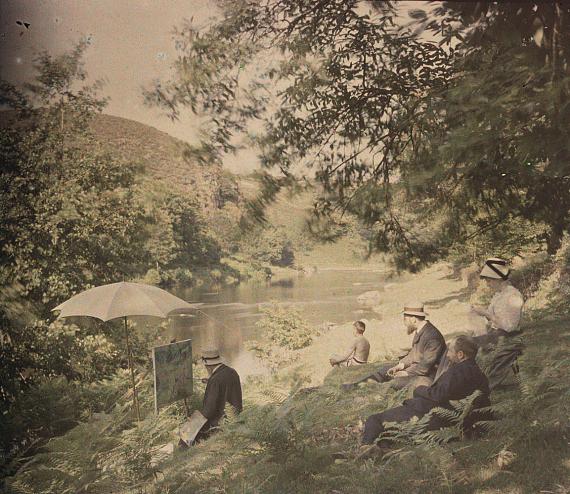

Armand Guillaumin Painting "Bathers near Crozant", ca. 1907

Autochrome (exhibited in facsimile)

9 x 12 cm

© Société française de photographie, Paris

A New Art: Photography and Impressionism

Eine neue Kunst. Photographie und Impressionismus

Olympe Aguado » Eugène Cuvelier » Alphonse Davanne » Louise Deglane » Robert Demachy » Peter Henry Emerson » Hugo Henneberg » Heinrich Kühn » Jacques-Henri Lartigue » Gustave Le Gray » Henri Le Secq » Charles Marville » Emile J. Constant Puyo » Henry Peach Robinson » Alfred Stieglitz » & others

Exhibition: 12 Feb – 8 May 2022

Museum Barberini

Humboldtstr. 5–6

14467 Potsdam

+49 (0)331-236014-499

info@museum-barberini.de

www.museum-barberini.de

Mon-Fri 10-19

Miss Mary Warner, 1910

Autochrome

24 x 18 cm

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

© ÖNB/Kühn

"A New Art: Photography and Impressionism"

Exhibition: 12 February — 8 May, 2022

In the nineteenth century, numerous photographers chose the same motifs as

impressionist painters: the forest of Fontainebleau, the cliffs of Étretat, or

the modern metropolis of Paris. They too studied different light effects, the passing

of the seasons, and changing weather conditions. Experimenting with composition

and perspective and using a range of different techniques, photography had

an artistic ambition from its beginnings. Until the First World War, its relationship

to painting was shaped both by competition and influence. Featuring more

than 150 works, the exhibition at the Museum Barberini explores photography’s

development to an autonomous art form and illuminates its complex relationship

to impressionist painting.

The new medium of photography was linked to both the industrial revolution and the

advent of a modern knowledge society. At the world’s fairs it was presented to an

international public. Photographic exposure and reproduction techniques served the

panoramic vision of the period and answered an encyclopedic desire to document.

The possibility of creating collections of any conceivable theme through photographs

corresponded to a new need to make knowledge accessible and to archive it. Similar

to the way in which the city centers of Paris, London, Vienna, or Munich were transformed

by historicizing architecture, the new medium also fused tradition and modernity:

museums, libraries, and archives were built, travelogues, surveys, and maps shaped the

era. At the same time as sociology became a subject, social documentary photography

emerged alongside novels of social realism. The natural sciences, which were now

becoming separate disciplines, described the present.

So what seemed more natural than to exploit photography’s exactitude? Might the new

medium become an auxiliary science of painting? In 1859, Charles Baudelaire wrote

a scathing critique of the first Paris Salon to include photographs. In a fictional dispute, he had a photographer say, "I want to represent things as they are, or rather as they would be, supposing that I did not exist." Against this, Baudelaire set the answer of a painter from his favored faction of 'imaginatives': "I want to illuminate things with my mind, and to project their reflection upon other minds." The antagonism between machine and mind established here by Baudelaire, a visionary and a friend of the impressionists, would continue for a long time. As late as 1936, Walter Benjamin’s reflections on the loss of the aura in "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" would return to this distinction.

Claude Monet, just like Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir,

worked en plein air in order to explore the new relationship between humans and nature.

The impressionists devoted their works to the fleeting moment, to the here and now,

each capturing the changing light and weather phenomena in their own way. This made

them natural allies of the photographers. Choosing the same motifs as the impressionists,

photographers too studied shifting light and atmospheric conditions and the passing

of the seasons. From the beginning, they pursued their artistic ambitions by experimenting with composition and perspective, using different techniques and materials, and employing blurring effects, dramatization, and montage. Like vision itself, light—the basis of photography—was a shared theme of painting and photography.

Before Photography: Painting and the Invention of Photography at the Museum of

Modern Art in New York made it clear that photography did not emerge from a scientific

context but from landscape painting. The medium’s perspectival and subjective nature

has been a research focus ever since, and the insights gained from this enabled pivotal

exhibitions such as Gustave Caillebotte: An Impressionist and Photography (Schirn, Frankfurt am Main, 2012) and The Impressionists and Photography (Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, 2019).

Yet the interplay between photography and impressionism remains underresearched.

A New Art: Photography and Impressionism at the Museum Barberini aims to address

this gap. Featuring more than 150 works, including photographs by Stéphanie Breton,

Auguste Hippolyte Collard, Eugène Cuvelier, Louis-Alphonse Davanne, Robert Demachy,

Peter Henry Emerson, Gustave Le Gray, Henri Le Secq, Heinrich Kühn, Charles Marville,

Constant Puyo, Henry Peach Robinson, Alfred Stieglitz, Carl Teufel, and Alphonse Taupin,

the exhibition illuminates the development of the new medium. Important loans have

been made by the Albertina in Vienna, the Serge Kakou Collection in Paris, the Münchner

Stadtmuseum, Musée d'Orsay in Paris, Museum Folkwang in Essen, Photoinstitut

Bonartes in Vienna, Société Française de Photographie in Paris, Staatliche Museen zu

Berlin, the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, and many other institutions.

Photography and Impressionism is the first photography exhibition to be shown

at the Museum Barberini since its opening in 2017. Its point of departure is the collection of impressionist and post-impressionist paintings by museum founder Hasso Plattner, which has been on permanent display since September 2020 and includes numerous

works by artists like Gustave Caillebotte, Claude Monet, or Berthe Morisot. The Von der

Heydt-Museum in Wuppertal, which will present the show from October 2, 2022 to

January 8, 2023 in cooperation with the Museum Barberini, is one of the institutions that

began to collect impressionist art early on, setting an example in both Germany and

Europe overall.

The exhibitions in Potsdam and Wuppertal are accompanied by a comprehensive catalog

published by Prestel, Munich, with contributions by Ulrich Pohlmann, Monika Faber,

Dominique de Font-Réaulx, Matthias Krüger, Esther Ruelfs, and Bernd Stiegler, which are

based on the findings of the preparatory symposium held in Potsdam in October 2021.

Pont de Grenelle, Paris, ca. 1875/76

Albumen print

34 x 42 cm

Bibliothèque de l’École nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Marne-la-Vallée

© École nationale des Ponts et Chaussées

"Eine neue Kunst. Photographie und Impressionismus"

Ausstellung: 12. Februar bis 8. Mai 2022

Im 19. Jahrhundert wählten zahlreiche Photographen die gleichen Motive wie die

Maler des Impressionismus: Den Wald von Fontainebleau, die Steilküste von Étretat

oder die moderne Metropole Paris. Auch sie studierten die wechselnden Lichtsituationen,

die Jahreszeiten und Wetterverhältnisse. Von Anfang an verfolgte die Photographie

durch Erprobung von Komposition und Perspektive sowie mit Hilfe unterschiedlicher

Techniken einen künstlerischen Anspruch. Ihr Verhältnis zur Malerei war bis zum

Ersten Weltkrieg sowohl von Konkurrenz als auch von Einflussnahme geprägt. Die

Ausstellung im Museum Barberini untersucht mit über 150 Werken die Photographie

um 1900 auf ihrem Weg zu einer autonomen Kunstform und beleuchtet ihr komplexes

Verhältnis zur impressionistischen Malerei.

Das neue Medium der Photographie war zugleich Teil der industriellen Revolution und

Beginn der modernen Wissensgesellschaft. Auf den Weltausstellungen wurde es einem

internationalen Publikum vorgestellt. Die photographischen Aufnahme- und Reproduktionstechniken bedienten sowohl den zeitspezifischen Blick als auch den enzyklopädischen Dokumentationswillen: Die Möglichkeit, mit Photographien Sammlungen beliebiger Themengebiete anzulegen, entsprach dem neuen Bedürfnis, Wissen zugänglich zu machen und zu archivieren. Wie die umgestalteten Stadtzentren von Paris, London, Wien oder München im Historismus der Architektur, so brachte auch das neue Medium Tradition und Moderne zusammen: Museen, Bibliotheken und Archive entstanden, Reisebeschreibungen,

Vermessung und Kartierung prägten das Zeitalter. Parallel zur Soziologie entstand neben

dem Gesellschaftsroman des literarischen Realismus die Sozialreportage in der Photographie. Die sich ausdifferenzierenden Naturwissenschaften beschrieben die Gegenwart.

Was lag somit näher, als die Exaktheit der Photographie zu nutzen? Sollte sich gar das

neue Medium zu mehr als einer Hilfswissenschaft der Malerei entwickeln? Zum ersten

Pariser Salon, auf dem auch Photographien ausgestellt wurden, schrieb Charles Baudelaire

1859 eine vernichtende Kritik. In einem fiktiven Streitgespräch ließ er einen Photographen sagen: "Ich will die Dinge so wiedergeben, wie sie sind, oder besser: wie sie wären, wenn ich nicht da wäre." Dagegen setzte Baudelaire die Antwort eines Malers aus der von ihm favorisierten 'Gruppe der Phantasiereichen': "Ich möchte die Dinge durch meinen Geist erleuchten und ihren Widerschein auf die anderen Geister abstrahlen." Damit legte Baudelaire, Vordenker und Freund der Impressionisten, den Antagonismus zwischenMaschine und Geist auf lange Sicht fest. Noch Walter Benjamins Überlegungen zumVerlust der Aura des "Kunstwerks im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit" aus dem Jahr 1936 geht auf diese Unterscheidung zurück.

Claude Monet wie Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro und Pierre-Auguste Renoir arbeiteten

unter freiem Himmel, um die neue Beziehung von Mensch und Natur zu thematisieren.

Die Impressionisten widmeten ihre Malerei dem Augenblick. Ihre Malerei war pure Gegenwart, die individuelle Reaktionen auf im Wechsel begriffene Licht- und Wetterphänomene thematisierte. Das machte sie zu Verbündeten der Photographen. Auch sie wählten die gleichen Motive wie die Impressionisten und studierten die wechselnden Lichtsituationen, Jahreszeiten und Wetterverhaltnisse. Von Anfang an verfolgten sie durch Erprobung von Komposition und Perspektive, mithilfe unterschiedlicher Techniken und Materialien sowie mit Unschärfe, Dramatisierung und Montage einen künstlerischen Anspruch.

Licht – Grundlage der Photographie – war wie das Sehen selbst gemeinsames Thema von

Malerei und Photographie. Die Ausstellung Before Photography. Painting and the Invention of Photography im New Yorker Museum of Modern Art verdeutlichte bereits 1981, dass die Photographie nicht aus dem Wissenschaftskontext hervorging, sondern aus der Landschaftsmalerei. Die Erforschung des perspektivischen und subjektiven Charakters

des Mediums stand seither im Fokus und ermöglichte so grundlegende Ausstellungen

wie Gustave Caillebotte. Ein Impressionist und die Fotografie (Schirn, Frankfurt am Main, 2012) und The Impressionists and Photography (Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid 2019).

Das Wechselspiel von Photographie und Impressionismus ist jedoch immer noch

unzureichend erforscht. Eine neue Kunst. Photographie und Impressionismus im Museum Barberini setzt hier an und beleuchtet mit über 150 Arbeiten, darunter Photographien von Stéphanie Breton, Auguste Hippolyte Collard, Eugène Cuvelier, Louis-Alphonse Davanne, Robert Demachy, Peter Henry Emerson, Gustave Le Gray, Henri Le Secq, Heinrich Kühn, Charles Marville, Constant Puyo, Henry Peach Robinson, Alfred Stieglitz, Carl Teufel und Alphonse Taupin, die Entwicklung des neuen Mediums. Bedeutende Leihgaben steuern die Albertina, Wien, Collection Serge Kakou, Paris, Münchner Stadtmuseum, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Photoinstitut Bonartes in Wien, Societe Francaise de Photographie, Paris, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, die Staatsgalerie Stuttgart und viele weitere Institutionen bei.

Das 2017 eröffnete Museum Barberini zeigt mit Eine neue Kunst. Photographie und

Impressionismus erstmals eine Ausstellung mit Photographien. Ausgangspunkt für dieses Thema ist die Sammlung impressionistischer und postimpressionistischer Gemälde

des Museumsstifters Hasso Plattner, die seit September 2020 dauerhaft in Potsdam

präsentiert wird und zahlreiche Anknüpfungspunkte bei Künstlerinnen und Künstlern

wie Gustave Caillebotte, Claude Monet und Berthe Morisot bietet. Das Von der Heydt-

Museum, das in Kooperation mit dem Museum Barberini die Schau vom 2. Oktober 2022

bis 8. Januar 2023 in Wuppertal zeigt, gehört zu jenen Häusern, die schon früh

impressionistische Kunst sammelten und damit nicht nur in Deutschland, sondern in

Europa Zeichen setzten.

Zu den Ausstellungen in Potsdam und Wuppertal erscheint bei Prestel, München, ein

umfangreicher Katalog mit Beiträgen von Ulrich Pohlmann, Monika Faber, Dominique de Font-Réaulx, Matthias Krüger, Esther Ruelfs und Bernd Stiegler, die auf den Erkenntnissen des die Ausstellungen vorbereitenden Symposiums im Oktober 2021 in Potsdam fußen.

After Sunset, 1898 or earlier

Gum bichromate

36 x 51 cm

© Photoinstitut Bonartes, Vienna

Gathering Water Lilies, 1886

Platinum print

19,5 x 29 cm

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung, acquired 1989, Rolf Mayer Collection, Stuttgart

© Photo: bpk / Staatsgalerie Stuttgart / Peter Henry Emerson