The hand that topples the tower

Mike Bourscheid » Vanessa Brown »

Exhibition: 6 May – 20 Aug 2023

Thu 13 Jul

CNA Centre national de l'audiovisuel

1b, rue du Centenaire

3475 Dudelange

+352-522424-1

Wed-Sun 12-18

"The hand that topples the tower"

Vanessa Brown and Mike Bourscheid

Exhibition: 6 May – 20 August 2023

During this summer season, the CNA is delighted to present The hand that topples the tower – a two-person exhibition by Vanessa Brown and Mike Bourscheid at Waassertuerm + Pomhouse. From 6 May to 20 August the two different artistic approaches will come together on the emblematic former industrial site in Dudelange to immerse the visitor in a multi-media experience.

In the exhibition space at the foot of the tower, Luxembourgish artist Mike Bourscheid will present his new photographic series Mutual Feelings through which he tackles the dichotomies that structure our vision of the world. The interior of the former water tank will be dedicated to the artist’s Sunny Side Up and other sorrowful stories, consisting of a projection of his new film Agnès, in which he takes on different roles, accompanied by sculptures presenting several costumes from the film. Meanwhile, the old pumping station Pomhouse will host Canadian artist Vanessa Brown's >>>000 / Gravity, which includes evocative projections and installations exploring the concept of holes as symbolic representations of human desire, the relativity of time, and our place in the galaxy.

Vanessa Brown

">>>000 / Gravity"

Gravity, gravitas. To have weight. To be held in place. >>>000 / Gravity by Vanessa Brown is an invitation, an affective installation that mediates the tension between the logics that govern our physical world (physics), those that govern our psycho-social space, and the desire to reach beyond both; to eclipse time and space.

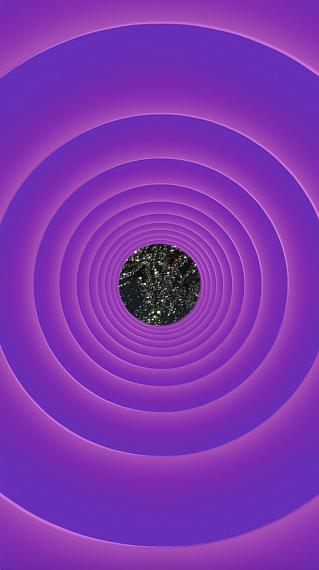

Three larger-than-life upright projections invite embodied engagement. Reference to the verticality of the cellular phone screen creates immediate experiential familiarity. Akin to scrolling, Brown’s captured and found images move from one into the other, overlayed precisely in a defined video collage. Although possible, the videos are not intended to be watched as discrete elements, but to be experienced in tandem with each other. The audio, a stunning commission by Michelle Helene Mackenzie, is similarly designed as a spatialized experience intended for bodies in motion.

Both the photocollage textiles and the moving video collages work with interstitiallity, those spaces between the real and the fantastic, or, as in the case of The Other Sun, the real and the ideal. In the titular video works, snow falls up, and surreal lunar-like landscapes are traced with the camera-eye. Scenes of scuba divers underwater and metalworkers pouring molten metal invite reflection on the solidity of reality, as instances where humans circumvent limitations, find holes to loop through.

As a portal between the "governed" world and the impossible, the fantastic, and the liminal one we all coinhabit to greater or lesser degrees, the Looney Tunes cartoon reappears throughout the three projections: as an animated, pulsating portal, or roadrunner unsuccessfully placing his famous black (escape) hole. At one point we watch While E. Coyote paint a road into solid rock. Roadrunner comes upon it unsuspectingly. With this moment of discovery played on loop, Roadrunner is destined to live the instant on repeat, leaving us to wonder if cartoon or real space dictates. Is this escape or entrapment?

When I was a kid, I used to have the very real feeling that I could breathe underwater. I was also certain that I lived a whole other life when I slept. This "other me" was completely knowable, I knew her age, how she dressed, where she lived. In >>>000 / Gravity, Vanessa Brown invites us to a world of portals, to contemplate the limits and possibilities of our experience. Most of all she invites us into experience. Imagine breathing iiiiiiiiin and then ouuuuut of a cartoon straw—the kind that, when you suck on it, you inhale the entire sky, and with it, the stars and planets. If you can imagine that, then you might be able to approximate how to say the title, >>>000 / Gravity.

Text by Sarah Nesbitt

Mike Bourscheid

"Mutual Feelings"

Sunny Side up and other sorrowful stories

Because the clown fell, his nose is red, colour of accident. Thus, "The smallest mask in the world" is a badge of clumsiness. It speaks of tumbles taken and blood spilt, of a life that does not go unscathed. In French, "se casser le nez" (to break one’s nose) means to fail. Like that of the clown, Mike Bourscheid’s multi-coloured nose expresses itself silently. Changing from blue to red, from yellow to green, it underlines an identity in flux. An identity one might even perceive as blinking, like a string of twinkling fairy lights, or a faulty bulb.

The nose is not the only organ imbued with a magic power. In the film Agnès, feet and hands have their own locks of hair. And though they don’t have a face, they are inhabited by an intentionality: they bawl each other out, help each other, form a community. Thus, Bourscheid lends to both organs and things a kind of non-human agency. In so doing, the artist blurs the distinction between object and subject. He lays bare the force inherent in things, what the philosopher Jane Bennett calls thing-power. Though matter may lack a beating heart, it is not lifeless for all that.

In fact, Bourscheid takes issue with the dichotomies that structure our vision of the world. Over and above the subject/object relation, he destabilizes, for instance, the opposition between human and animal. In the photo series Mutual feelings, the resulting bewilderment generates the unknown. We find ourselves confronted with what as yet has no name.

The hairy creature posing in front of the camera may seem like a werewolf, but she is also made-up, manicured and hairstyled. This juxtaposition of codes thwarts our expectations. It has to be said, the monstrosity that Bourscheid portrays is neither hideous, outrageous, nor extremely cruel. It simply eludes definitions and stereotypes. Hence, it throws us off balance. In fact, monsters are not necessarily bloodthirsty creatures, just unknowable: they do not exist in language. And moreover, if we insist on wanting to name them, we run the risk, as Derrida warns, of transforming them into puppets.

So instead, let us circumscribe them and admire, rather, the systems of interference that Bourscheid puts in place by way of the silent power of costumes and accessories. By questioning the structuring oppositions that rule our relationship to the world, Bourscheid forces us to read the real differently.

Text by Daphné B.