Shigeyuki Kihara »

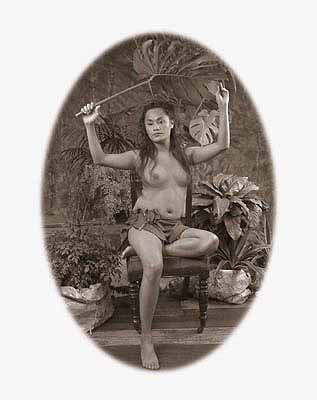

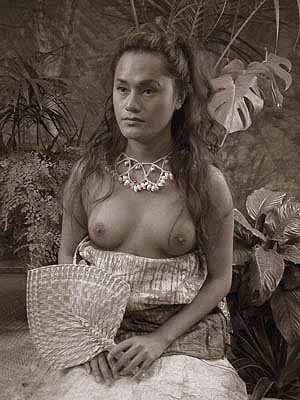

Fa'a Fafine: In the Manner of a Woman

Exhibition: 10 Mar – 2 Apr 2005

Sherman Galleries

16-20 Goodhope St . Paddington

NSW 2021 Sydney

Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation

16-20 Goodhope St . Paddington

NSW 2021 Sydney

+61 2-93311112

Wed-Sat 11-17

The self-effacement of Shigeyuki Kihara Painters who portray themselves are subject to their own scrutiny, limited by how they use the tools and materials of their work as well as by their propensity for accuracy. The same could be said of artist Shigeyuki Kihara, who is the subject of her own artwork and co-opts technicians to realise the outcome. Her photographic work is a collaborative process reliant on a cameraman and makeup stylist whom she presides over and directs. In Fale Aitu (House of Spirits), 2003, Kihara transforms herself into seven distinct personas of her own construction and fantasy, alluding to the comedic skits that are performed by males at Samoan festivals. Similarly, in Vavau (Tales of Ancient Samoa), 2004, she features herself as seven legendary Samoan characters. Kihara is aware of the work of Cindy Sherman, Yasumasa Morimura, the calculated artifice of Tracey Moffatt’s Something More, 1989, and Lisa Reihana’s fictive still photographs of Maori history, Native Portraits n. 19897, 1998. Rather than identifying with this genre of photographic practice, Kihara has shaped her own creative path by grappling with the personal politics of self and identity. Shigeyuki Kihara was born in Samoa in 1976, to a Japanese father and Samoan mother. She lived for five years in Indonesia, seven years in Japan, and arrived in New Zealand via Samoa in 1991. She studied fashion design at Massey University, Wellington. In her second year she won a national student fashion award with Graffiti Dress, 1995, purchased by the National Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa. Some years later the museum purchased a line of twenty-eight ready-to-wear T-shirts from Kihara’s exhibition, Teuanoa’i (Adorn to Excess), 2000. Related to her Sherman Galleries exhibition, Fa’a Fafine (In a Manner of a Woman), Kihara undertook two projects that both appropriated and deconstructed found images. Black Sunday, 2001, consists of eleven inkjet prints on stretched canvases. Pastel coloured T-shirts are collaged onto ethnographic images from the South Pacific, reclaiming history by tagging them with consumer wear, lipstick and sunglasses. Savage Nobility is an eight-page fashion editorial for which Kihara was the stylist and one of the models. The results mimic the postcolonial imaging of Polynesians. Postmodern theorist Judith Butler argues that it is not possible to be a human subject without taking shape within the law of a gender – either male or female. This exclusionary framework creates a domain of the ‘unlivable’, occupied by people who do not fall into the binary divisions of gender. Either they live in secret and ‘pass’ as if they belong to one or other category, or they are dehumanized. It is the latter realm that is occupied by Kihara, who lives her life as a transgender. Butler’s theories ignore the role that race and ethnicity plays in human subject-hood and are limited by a western construct of thinking. Kihara, to some extent, has been protected from these understandings by her early assignation in Samoa as a fa’a fafine, who are born biologically male and express feminine gender identities in a variety of ways – an accepted role in Samoan society. Fiona Foley’s Native Blood, 1994, preempts an aspect of Kihara’s current work. Both artists use as their template the colonial photographic postcard representation of the languid, reclining South Seas Belle and position themselves in a comparable situation. Whereas Foley’s portrayal focuses on changing the power balance of such material and reclaiming the boundaries of the colonial gaze, Kihara’s re-enactment has a fidelity to detail and, at face value, pays tribute to both the kitsch aspect of the genre and the sexualised Dusky Maiden. There is a seriousness in Kihara’s posturing that undermines the irony she may wish to invoke or the truth she wishes to declare – a sense of ‘passing’ as a woman or as a man impersonating a woman, as opposed to the woman who is a man impersonating a man. Kihara’s artwork straddles an ambiguous field of binary forces – east/west, original/copy, male/female – and challenges the viewer as being complex and multiple, parody and reality. ‘Who am I, what am I, and what are you?’ are questions that will never haunt or torment Kihara. Rather, they provide her with the material for her artwork. The possible answers to these questions are always limited and draw boundaries that Kihara will continue to cross in the expression of her existence. Jim Vivieaere Artist and curator based in Auckland