Jeff Cowen »

Exhibition: 29 May – 31 Jul 2008

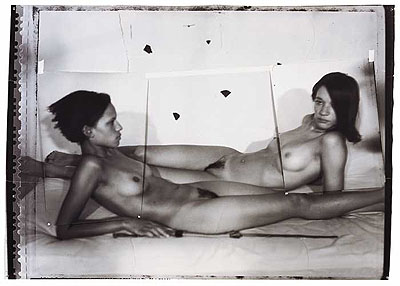

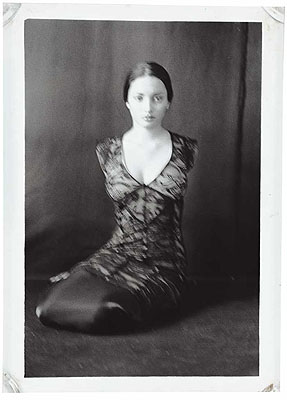

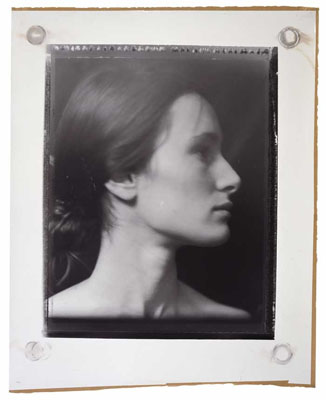

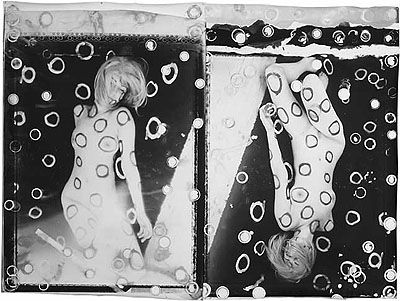

Extract of text by Urs Albrecht from the exposition catalogue "Jeff Cowen" I remember my first encounter with Jeff Cowen's photographs. It was autumn 2004, at the Parisian Galerie Seine 51. I was both moved and fascinated by the two children of Puerto Rican descent on the New York ferry, whom I took to be brother and sister. The girl is older than the boy and holds him tightly in her arms. Her gesture is not exactly protective; she seems to be saying, "Look, he's mine". This impression is reinforced by the fact that her left leg also lies across the legs of the boy. The embrace is typical of couples in love. The photograph was taken at a close distance, with a small-format camera and probably a 50 mm lens, in daylight. In the background we see the head and shoulders of someone curled up in a seat, whose wavy hair seems to fall on that of the children, which we find slightly disturbing. One would even prefer to move that person aside, however she plays an integral role in the image, granting it authenticity. What we see is a snapshot, in other words, an instant captured by the camera. The pose probably hasn't changed, what has changed is the gaze of the couple. The two children were looking at the photographer; now they're looking at us, a double pair of eyes, almost at the same height. There's a world of difference in a photograph between a person who looks at the camera and one who looks away. By confronting the camera, as does the young couple, they are transformed from object of the camera to the subject. Thereby it is as if the photographer has disappeared and has been replaced by us the observer. A dialogue ensues. We meet the warm and questioning gaze of the girl, who nonetheless still maintains her distance, while the little boy looks at us unpretentiously. Eyes in which we can still sense the last traces of a childhood tinged by sadness and the hardships of life in the big city. Eyes that have already seen far too much. To the left of the young couple hung a photograph of a car in flames, a Jaguar. The scene is photographed at night, from above. As I looked more intensely I realized that the headlights were still on. I shuddered; what had happened to the passengers? How does one manage to photograph such a scene? It was no doubt taken by someone used to scouring the city's crevices. To the right of the photograph of the children hung a nude, Untitled, 1989. A young woman with a feline air arches her beautiful back, raising her bottom that almost brushes the upper edge of the photo. Her chin rests on one hand and she holds a cigarette in the other. The languorous and sexy position is so real and full of life and yet at the same time it breathes the stale air of death. Jeff Cowen's New York series belongs to the most revealing that I have seen about this city. The photos are strong, poetic and sensuous; and are taken at a very short distance from the events, from the people. Jeff Cowen's move to Paris and later to Berlin enhanced his work in Art Photography. In addition to his reportage work from Cuba, he created images inspired by late nineteenth-century photography, which were in turn inspired by the painting of that period. Cowen's images are free and whimsical pictures brimming with allusions, in which he attempts time and again to cross certain boundaries. He strives to overcome the flatness of the photographic image. He tears them and he puts them together again. He tries to give them body. The photograph becomes an object. He is also directly involved in the printing process. He smears and splatters chemicals to also create 'abstract paintings'. In these darkroom interventions he puts himself in the photograph one more time. Thanks to these physical traces the portraits seem to be charged with energy. The gain in expression is remarkable. A particularly scandalous photograph is the one entitled Sophie 2, a nude on horseback, her face covered by a gas mask. The animal's back and the mask highlight the nudity, making it almost physically experienceable. The mask, an allusion to the world of sadomasochism, also represents the head of the horse, which cannot be seen. The gas mask is a foreign body, so much so that we are irremediably attracted to the image and at the same time shocked by it. However, the fact that the nude is mounted on a horse heightens the perverse duality of the work, thereby transforming the image into an icon. Among the nudes we discover idealized portraits of girls and women. These female archetypes seem to come from another world and yet are strangely familiar to us, as if they had always inhabited our innermost being. Jeff Cowen has created a corpus of timeless, independent and insightful images that stand as a rock in the tide of contemporary photography. The waves of fashion, always fleeting, can have no effect on it. Urs Albrecht

Recuerdo mi primer encuentro con las fotografías de Jeff Cowen. Fue en el otoño de 2004, en la Galerie Seine 51, de París. Me emocionaron y fascinaron entonces los dos niños de origen portorriqueño en el transbordador de Nueva York; hermano y hermana, supuse. La niña es mayor que él y lo estrecha con fuerza entre los brazos. No es el suyo un gesto exactamente protector; más bien parece decir: "Mirad, es mío". Refuerza esta impresión el hecho de que tenga la pierna izquierda encima de las piernas del niño. Es el abrazo típico de las parejas de enamorados. La fotografía se tomó a poca distancia, con una cámara de pequeño formato y un objetivo probablemente de 50 mm, con luz diurna. Detrás vemos la cabeza y los hombros de alguien que viaja encorvado en su asiento. Molesta un poco la melena ondulada que parece caer sobre el pelo de los niños. Nos gustaría hacer a un lado a esa persona, que, sin embargo, es parte integrante de la imagen; le confiere autenticidad. Lo que vemos es una instantánea; en otras palabras, un momento capturado por la cámara. La pose no ha cambiado; lo que ha cambiado es la mirada. En aquel instante, los dos niños miraban al fotógrafo; ahora nos miran a nosotros. Son dos pares de ojos casi a la misma altura. No es lo mismo que la persona retratada mire a la cámara o hacia otro lado; en una fotografía, la diferencia es grande. Si se enfrenta a la cámara, como hacen los dos niños, pasa de objeto a sujeto. Es como si el fotógrafo hubiera desaparecido y lo hubiéramos sustituido nosotros, los observadores. Se inicia un diálogo. Encontramos la mirada cálida e inquisitiva de la niña, que, no obstante, mantiene las distancias; por su parte, el niño nos mira con naturalidad. Ojos en los que aún percibimos los últimos restos de una infancia teñida por la tristeza y las penurias de la vida en la gran ciudad. Ojos que ya han visto demasiado. A la izquierda de los niños colgaba la fotografía de un automóvil en llamas, un Jaguar. La escena está fotografiada de noche, desde arriba. Al mirarla con más detenimiento me di cuenta de que los faros todavía estaban encendidos. Me estremecí; ¿qué les había pasado a los ocupantes? ¿Cómo se llega a fotografiar algo así? Sin duda, debió de hacerlo alguien acostumbrado a batir los desfiladeros urbanos. A la derecha de la fotografía de los dos niños había un desnudo, Untitled, 1989. Una joven de aire felino enarca su hermosa espalda y levanta el trasero, que roza, casi, el borde superior de la fotografía. En una mano apoya el mentón; en la otra tiene un cigarrillo. La pose, lánguida y sexy, es sumamente real, está llena de vida, pero al mismo tiempo respira el aire rancio de la muerte. La serie de Nueva York de Jeff Cowen está entre las más reveladoras que he visto sobre esta ciudad. Son fotos duras, pero también poéticas y sensuales, y están tomadas a muy poca distancia de los sucesos, de la gente. El traslado de Jeff Cowen a París, y más tarde a Berlín, enriqueció su trabajo en el ámbito de la fotografía artística. Además de un reportaje sobre Cuba, creó imágenes inspiradas en la fotografía de finales del siglo XIX, que, a su vez, se inspira en la pintura de esa época. Las imágenes de Cowen son libres y caprichosas, rebosantes de alusiones; en ellas, el fotógrafo intenta cruzar una y otra vez ciertos límites. Se esfuerza por superar la dimensión plana de la fotografía: rasga las fotos, vuelve a unir las partes, trata de darles cuerpo. La fotografía se convierte en objeto. Interviene directamente en el proceso de revelado. Embadurna y salpica con sustancias químicas para crear también "pinturas abstractas". En esas intervenciones en el cuarto oscuro, se introduce en la imagen una vez más y gracias a esos rastros físicos, los retratos parecen cargados de energía. La expresividad aumenta de manera notable. Una fotografía especialmente escandalosa es la titulada Sophie 2, un desnudo montado a caballo, el rostro cubierto con una máscara antigás. El lomo del animal y la máscara realzan la desnudez y la hacen casi físicamente experimentable. La máscara, una alusión al mundo del sadomasoquismo, representa también la cabeza del caballo, que no se ve. La máscara antigás es un cuerpo extraño; hasta tal punto, que la imagen nos atrae sin remedio y, al mismo tiempo, nos impacta. Sin embargo, el hecho de que el desnudo monte a caballo intensifica la perversa dualidad de la obra y, así convierte la imagen en icono. Entre los desnudos descubrimos retratos idealizados de niñas y mujeres. Arquetipos femeninos que parecen venir de otro mundo y que, no obstante, nos resultan extrañamente familiares, como si hubieran habitado desde siempre en lo más íntimo de nuestro ser. Jeff Cowen ha creado un corpus de imágenes atemporales, independientes y penetrantes que se alzan como una roca en el oleaje de la fotografía contemporánea. Las olas de la moda, siempre fugaces, no pueden afectarlo. Urs Albrecht