Rössler-Wiskovsky-Funke

Tres maestros de la vanguardia Checa

Jaromír Funke » Jaroslav Rössler » Eugen Wiskovsky »

Exhibition: 25 Sep – 5 Dec 2008

Kowasa Gallery

Mallorca 235

08008 Barcelona

+34 (0)93-4873588

galeria@kowasa.com

www.kowasa.com

Tue-Sat 16:30-20:30

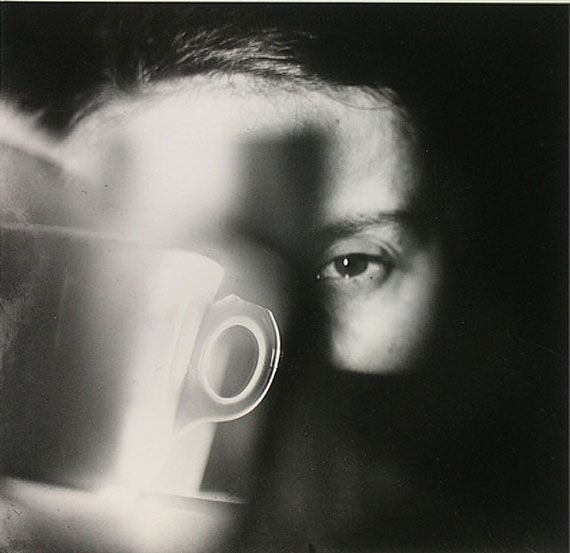

Untitled (Portrait of Gertruda Rösslerova with cup)

Ca. 1923/1991

KOWASA gallery opens the season 2008-2009 with an exhibition that pays tribute to Jaroslav Rössler, Eugen Wiskovský and Jaromír Funke, three of the most distinguished members of the Czech Avant-garde (1920-1960). Four portfolios edited by the Prague House of Photography provide a recollection of the most significant moments in the trajectory of the three photographers. The photographic genius of Jaroslav Rössler (1902-1990) was rescued from oblivion in the late sixties when his astoundingly early contribution to the history of Czech photography and the panorama of the international avant-garde finally became acknowledged. Forty years earlier, in the twenties, Rössler had been one of the first photographers in contact with the Czech Modernity. But Rössler had also been a key figure in the history of international photography, a pioneer in the company of Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy, Alfred Langdon Coburn and Christian Schad. Gifted from nature with a highly complex idiosyncrasy, Rössler encountered the expressive balance for his introversion among the longings of a compulsive imagination and the rational constructs of his visual universe. Having become apprentice of Frantisek Drtikol at the early age of 14 and until 1925, Rössler was about to liberate the image from its fixation to the model. His eagerness with experimentation entered in close synergy with the ideals of Poetism, the most progressive anti-academic movement of Prague at that period. This fact becomes more than evident in the early cubo-fututist compositions (1922), through which the 20-year old Rössler anticipated Constructivism and New Objectivity. Rössler stands out for his pragmatic conceptions. In dynamic compositions he investigated the possibilities of interaction between photomontage, collage, photogram and graphic media. Anticipating Lettrism, Rössler freed typography from verbal message, played with light and projected shadow, experimented with transparency, solarization, mirror reflections, overexposure and unusual angles. In his hands, common objects such as a jar or a radio obtained unexpected plastic dimensions, reaching a dreamful minimalism that reveals the purist possibilities of photographic abstraction. Similarly to creators as Man Ray o Lázsló Moholy-Nagy, the poetic constructivism of Jaroslav Rössler was not delimited solely in his artistic practice but imbued instead his commercial activity in advertising, portrait photography and theatre. The last decade of his creative trajectory are characterized by a spirit of free and uncompromising experimentation in the verge of a postmodern sophistication: Rössler did not hesitate to reinvent himself, by recycling his old negatives, by combining and by overexposing realist with abstract imagery. Contemporary with Rössler, Jaromír Funke (1896-1945) did not just merely emerge as the leading member of the Czech avant-garde in the twenties and in the thirties, but he was also a distinguished theoretician, editor, photography professor and co-founder of the Photographic Society of Prague. In the late 1910s, Funke gave his first steps as an amateur photographer in the small city of Kolin nad Labem, but soon his art entered a transition from Pictorialism towards a highly radical kind of abstract approach. Through his writings and photographs, Funke contributed his own vision of modern photography, a solid intellectual posture in accordance with the doctrine of Photogenism that challenged procedures based on manipulation or even the elimination of the photographic apparatus, such as the photogram and photomontage. Funke was a fierce defender of Straight Photography and emphasized the capability of the camera lens to generate illusion and magic through the play of light and objects within reality. His series "Time Persists" created as his response to Atget's documentary photographs introduced by the Surrealists include some of the best practical applications of his Photogenism. Images, such as "The Eye" (1929), put into evidence how a magic and direct vision of reality is possible without the mediation of photomontage and other tricks. The compositions of Jaromír Funke are improvisations based on the most simple forms and media, but, above all, they play with shadow. The projected shadow reached with Funke at its extreme as a ghostly appearance expressing the poetry and lyricism inherent in the Czech art. The artist summarized his posture in 1940 in his essay "From Photogram to Emotion": "The beginning point and the objective is emotion, an emotion in a certain sense, something like a dream, where human fantasy is laid open and fairy tale-like rifts are mastered. Fairy tales, indeed, but created out of a photographic reality. A human dream, photographed in order to relate it to others." The work of Eugen Wiskovský (1888-1964) is extensive neither in volume nor in subjects but it is strong in originality, meticulous elaboration and conceptual profoundness. Although Wiskovký combined his lifelong and passionate affiction to photography with his work as a grammar school teacher, translator and –in the forties- editor of a photography magazine with Josef Ehm, in retrospective he emerges as one of the most singular figures of the Czech modernity. His engagement with photography began when he was 15 years old but it was only in the twenties when his artistic practice reached its peak thanks to his friend Jaromír Funke in Kolin nad Labem who familiarized him with the doctrines of the New Objectivity and Constructivism. Inventiveness and improvisation with objects and textures are the principal characteristics of Wiskovský's oeuvre, an oeuvre guided by the conviction that "the most uncommon the content, the most uncommon has to be representation". Wiskovský sustained the distancing of photography from the other visual arts and their representation canons. In the forties, his interest in landscape pushed him to take pictures of Prague's surrounding areas, as Josef Sudek would do some years later. These symbolically charged landscapes arisen from the sphere of imaginary express Wiskovský's ideal that even in a landscape photograph "the process is possible which gives dead real mass a soul, a unifying idea, which brings the picture in life".

Lunar Landscape

1929/1992

Eye

Al dorso a lápiz

Portfolio IV, 1995. Prague House of Photography