Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie »

Portraits Against Amnesia

Exhibition: 22 Aug – 20 Sep 2003

Andrew Smith Gallery

330 South Convent Ave

AZ 85701 Tucson

+1-505-699.3898

info@andrewsmithgallery.com

www.andrewsmithgallery.com

Tue-Sat 11-17

"Whether Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie is documenting or reclaiming histories and images, commenting on national and global politics, or making us laugh, her voice is strong and clear." Veronica Passalacqua

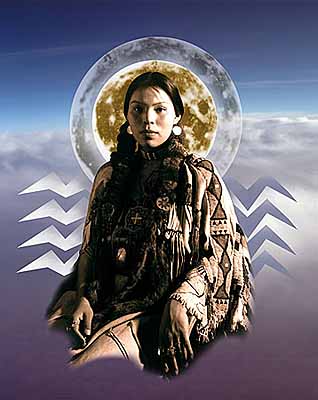

Andrew Smith Gallery at celebrates Indian Market 2003 with an exhibit of photographs by Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie titled "Portraits Against Amnesia," opening Friday, August 22, 2003, with a reception for the artist from 5-7 p.m. The exhibit contains ten 20" x 30" photographic portraits that combine imagery from vintage photo postcards of Native Americans that Tsinhnahjinnie has enlarged and manipulated digitally. Recently announced as a 2003 Eiteljorg fellow with the prestigious Eiteljorg Museum of American Indian and Western Art in Indianapolis, Tsinhnahjinnie is a seminal figure of the first generation of Contemporary Native photographers. For over thirty years her art has imbued the complex issues of identity with intelligence, wit and grace. Tsinhnahjinnie's speaks to a Native audience, without apology to the "mainstream." Her graphically powerful works range from biting satires to moments of indigenous conceptuality. The exhibit continues through September 20, 2003.

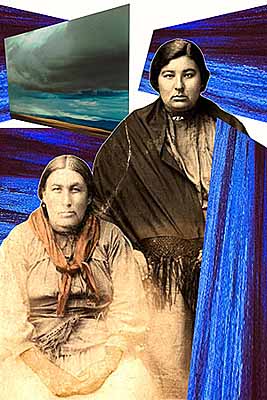

To produce her series, "Portraits Against Amnesia," Tsinhnahjinnie acquired turn of the century photo postcards, 19th and 20th century Native consumers hiring portrait photographers to record their image, portraits initiated by the sitter, as they envisioned themselves. The "mainstream" art market for Indian portraiture, she reminds us, is primarily interested in the tenacious stereotype of Indians not of Native people choosing their own contemporary expression.

"Grandma," is a portrait of Tsinhnahjinnie's Seminole grandmother. A young woman stands before the camera wearing a dress stylish in 1913; she is surrounded by transparent yellow dots that dance about her enigmatically. According to Tsinhnahjinnie, these dots represent "the spirits that help you before you enter this world, the spirits that help you while you're in this world, and the spirit that you will become."

Tsinhnahjinnie’s layering of time/perception combined with abstract imagery, symbols, personal references from her own life creating "Zona Indigena" a rich landscape of Nativeness.

In the image titled, "Dad," Tsinhnahjinnie enlarged a photograph of her father wearing WWII Army Air Force fatigues, surrounded by samples of his own artwork, the duality of maintaining one's personal world and American politics are presented in this piece.

In "Istee-cha-tee Aspirations," a young man with short hair and glasses, wearing a white shirt with a bow tie, and conventional trousers poses before the camera. His hand rests on his hip and his foot rests on a chair. Tsinhnahjinnie cast a transparent colored circle around the young man's hand with the thumb extended as it grasps the chair. His assertive posture and indirect way of pointing with his thumb appears political according to Tsinhnahjinnie, resembling "a gesture that former President Clinton often utilized."

In "Grandchildren" Tsinhnahjinnie speaks of her Oklahoma Seminole relatives, thus opening up issues of hybridity ". . . history is often hidden," she says, "so in 'Grandchildren' I raise the issue of interracial relations that are put into selective memory, conveniently forgotten."

Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie was born in 1954 into the Bear and Raccoon clans of the Seminole and Muskogee Nations. Born for Tsinajinnie Clan of the Dine' Nation. She grew up in Phoenix and Rough Rock, Arizona, and later attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. She received her B.F.A. from California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland in 1981 and was a Chancellor’s Fellow at from University of California at Irvine for her MFA. Tsinhnahjinnie has taught at the University of California at Davis, San Francisco State University, San Francisco Art Institute and the Institute of American Indian Art. Her numerous bodies of work including "Native American and Hawaiian Women of Hope" (1997), "Metropolitan Indian Series" (1984), "Nobody's Pet Indian" (1993), "Memoirs of an Aboriginal Savant" (1994), "The Damn Series" (1997), and a video installation, "Aboriginal World View" (2000), have been exhibited nationally and internationally.