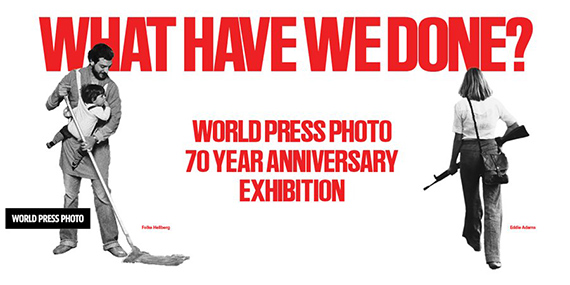

What Have We Done?

Unpacking Seven Decades of World Press Photo, curated by Cristina de Middel.

Eddie Adams » Harry Benson » Eric Bouvet » David Chancellor » William Daniels » Corinna Dufka » Horst Faas » Johanna-Maria Fritz » Robin Hammond » Mustafa Hassouna » Don McCullin » Steve McCurry » Georges Merillon » Christopher Morris » James Nachtwey » David Parker » Adam Pretty » Shobha » John Stanmeyer » Tom Stoddart » David Turnley » Klaas Jan van der Weij » Francesco Zizola » & others

Festival: 20 Sep – 19 Oct 2025

The Market Photo Workshop

138 Lilian Ngoyi St, Newtown

2001 Johannesburg

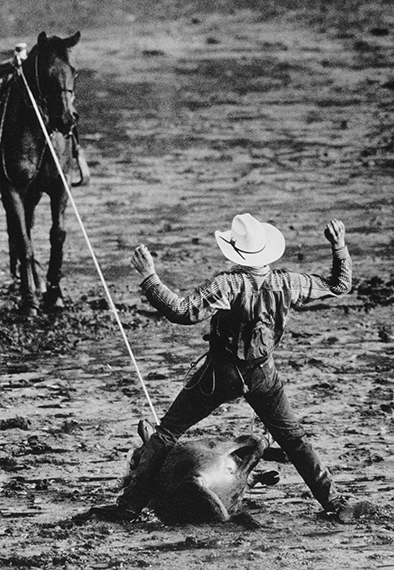

04 - Being a Man "01 January, 1994

For the rodeo cowboys traveling around America, the rodeo is not just a hobby or a job: it is a way of life. They spend most of their time on the road between one event and the next, planning their lives around the rodeo calendar. For some, it is not unusual to take part in more than 100 rodeos a year all over the US and Canada. Today's competitive rodeo, where skills like lassoing and broncobusting are demonstrated, finds its origin in the cattle ranches of the Wild West."

70th anniversary World Press Photo

major exhibition curated by Cristina de Middel

and Pop-up Festival

Groningen, the Netherlands

From 19 September to 19 October

Johannesburg, South Africa

From 20 September to 19 October

Dhaka, Bangladesh

From November

...

In 2025, World Press Photo marks its 70th anniversary. To mark this occasion, and as part of a series of special events across 2025, World Press Photo presents What Have We Done?, an exhibition curated by artist and photographer Cristina de Middel. To take place in Groningen, Johannesburg, and Dhaka, the exhibition aims to deepen and challenge one’s understanding of how images construct meaning, promoting a more nuanced engagement with visual storytelling.

By examining archival images and their contexts, we acknowledge the remarkable work done by journalists in often very challenging circumstances, while simultaneously inviting the public to engage with our visual past not as a fixed narrative, but as a living resource that informs how we might tell stories differently.

Reflecting on the 70th anniversary has brought World Press Photo back to our extensive archive spanning seven decades of stories that have been powerful vehicles of change. Still, delving deeper into the archive, we have also had to confront the unintended consequences of our choices, whether from assumptions made or voices that were underrepresented. This exhibition is an invitation to reflect on the various recurring visual patterns that are to be found in different eras and to start a dialogue.

Featuring over 100 photographs from those working across the 70 years – from Horst Faas, Don McCullin, David Chancellor, Eddie Adams, and Steve McCurry, to Johanna Maria Fritz and Sara Naomi Lewkowicz – the exhibition is organized around six recurring visual patterns identified in World Press Photo’s extensive archive:

Visitor information

The world premiere of What Have We Done? will take place from 19 September to 19 October 2025 at Niemeyer in Groningen, and is hosted by Noorderlicht—one of the Netherlands’ leading platforms for photography and lens-based media. It will also be shown in Johannesburg, South Africa, at The Market Photo Workshop from 20 September, and in Dhaka, Bangladesh, at Drik Picture Library from November.

Running alongside What Have We Done? are pop-up festivals in each location, which will bring together critical thinkers, photographers, and speakers for a dynamic program of talks, presentations, workshops, guided tours, and educational activities – all aimed at deepening engagement with the exhibition’s themes and sparking meaningful dialogue. The complete programs will be shared soon.

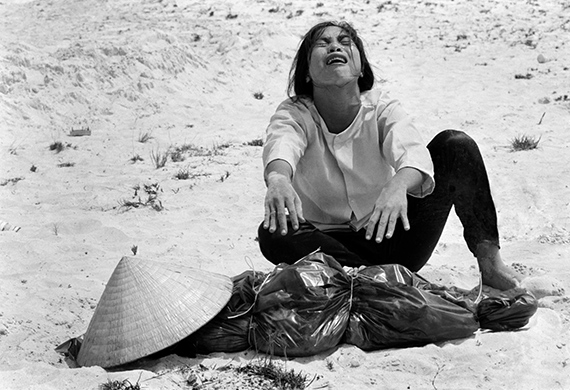

01 - Weeping Woman "01 January, 1989

Chaos reigns the streets at the funeral procession for the Ayatollah Khomeini, who died at the age of 89. Among the millions of mourners giving free reign to their grief, several people were crushed to death; many more fainted and suffered injuries."

Weeping Women and Men Rescuing

The stories told in the archive often follow a pattern: women weep, men rescue. These repeated images aren't random – they reinforce traditional ideas about who's vulnerable and who's strong. We see tear-streaked female faces, frozen in grief, while men are captured mid-action, carrying the wounded, giving orders, pulling others from danger. Without saying a word, these pictures shape how we think about gender roles during disasters, conflicts, and tragedies.

Emotional Soldiers and Debris

Press coverage of war often follows a familiar script, shaping perception rather than revealing the full reality. White soldiers, predominantly, appear in the archive in moments of exhaustion or contemplation – images that humanize them while leaving their actions on the battlefield unseen. Soldiers with darker skin are more frequently shown in combat, reinforcing narratives of aggression and dehumanization. These choices create an imbalance in documentation, influencing who appears as a victim and who is framed as a threat.

At the same time, destruction is often aestheticized. War debris transforms into striking compositions, distancing viewers from the human toll of violence. This visual approach echoes Hollywood's cinematic language, where conflict is dramatized and romanticized, making it easier to digest.

By emphasizing soldiers' emotional burdens while abstracting the consequences of their actions, these images shape a narrative that simplifies war, making it familiar rather than unsettling.

Being a Man and Being a Woman

Media representations create distinct visual worlds for men and women. Men consistently appear as figures of action and authority – triumphant athletes, determined leaders, protective forces during crises. These images celebrate physical strength, decisive movement, and professional achievement.

Women, by contrast, occupy more limited visual roles. They appear as decorative elements, emotional responders, caregivers, or objects of desire. Even when portraying professional women, visual framing often emphasizes appearance over competence. In tragedy, women become symbols of suffering rather than agents of change.

These visual patterns reflect deeply embedded storytelling traditions. Repeated across decades of news imagery, they normalize specific gender expectations – reinforcing who acts and who reacts, who shapes events, and who experiences them. These contrasting visual languages don't merely reflect society but actively shape our understanding of who belongs in which spaces and roles.

Black Skin and The Dark Continent

Western media and culture have long framed Africa as an exotic and unknowable place – a dark continent rather than a Black one. This perspective is reinforced through recurring visuals: leaders portrayed in ways that undermine their authority, an overwhelming focus on war, famine, and suffering, and a scarcity of stories that build respect, nuance, or confidence in a continent far more complex than these narratives suggest.

Equally persistent in the World Press Photo archive is a fascination with Black skin itself. Close-ups linger on its texture as if observing something unfamiliar, echoing colonial-era representations where African bodies were treated as specimens rather than individuals. This aesthetic curiosity, combined with a limited and repetitive visual language, continues to shape how Africa and its people are perceived, reducing a vast and diverse reality to a narrow and distorted frame.

Silhouettes and Shadows - The ‘Wow’ Moment

Photographers are trained to see what others miss — a fleeting silhouette, a momentary shadow, a perfect collision of form and light. Whether capturing the ecstasy of a goal or the chaos of a war zone, their skill lies in freezing time at its most expressive. This pursuit of the decisive moment — that impossibly balanced instant — is what gives photography its power, and its pleasure. But the same tools that elevate one kind of story can complicate another.

The use of beauty — of carefully composed frames, cast shadows, dramatic contrasts, and aesthetic precision — in images of conflict or suffering raises difficult questions. When does visual impact deepen our understanding, and when does it risk turning pain into spectacle? In these contexts, beauty can create distance, rendering horror strangely palatable, even poetic. It can help make sense of chaos — or obscure the truth of it.

Fire and Smoke

Fire and smoke have long been symbols of chaos and transformation – whether in ancient myths, biblical visions of hell, or the burning cities of history. In photojournalism, they serve as unmistakable markers of crisis, turning moments of conflict and disaster into powerful, almost elemental imagery. A cloud of smoke on the horizon signals destruction before we even know the details.

But fire doesn't just document events – it shapes how we remember them. Its presence in an image adds weight, a sense of urgency, and sometimes even a kind of tragic beauty. As these visuals repeat over time, they become part of an established language of drama, reinforcing how we picture upheaval and loss.

06 - The Dark Continent "09 December, 2013

In March, an alliance of mainly Muslim rebel groups known as Séléka seized power in the Central African Republic (CAR). Hundreds were killed, and some 400,000 people displaced, as violence in the CAR escalated.

01 - Weeping Woman "11 April, 1969

A Vietnamese woman cries over the body of her dead husband, who was discovered with 47 others in a mass grave. Remnants of the corpse were wrapped in plastic. She identified her husband by examining teeth and covered the skull with her hat.