The Vision of the Other: Modernity and the Photographed Face

La Visión del Otro - Modernidad y rostro fotografiado

Dimitry Baltermants » Eva Besnyö » Ilse Bing » Henri Cartier-Bresson » Francesc Català-Roca » Agustí Centelles » Václav Chochola » Joan Colom » Denise Colomb » Robert Doisneau » César Domela » František Drtikol » El Lissitzky » Nat Finkelstein » Eugeni Forcano » Florence Henri » Lucien Hervé » Emil Otto Hoppé » Horst P. Horst » George Hurrell » Izis (Israelis Biedermanas) » Yousuf Karsh » Tony Keeler » André Kertész » Edmund Kesting » Jacques-Henri Lartigue » Man Ray » Guido Mangold » Ramón Masats » Oriol Maspons » Willy Maywald » Xavier Miserachs » Tina Modotti » Ugo Mulas » Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) » Arnold Newman » Ruth Orkin » Roger Parry » Leni Riefenstahl » Alexander Rodchenko » Alberto Schommer » Edward Steichen » Paul Strand » Josef Sudek » Karin Székessy » Maurice Tabard » Marc Trivier » George S. Zimbel »

Exhibition: 11 Mar – 16 May 2009

Kowasa Gallery

Mallorca 235

08008 Barcelona

+34 (0)93-4873588

galeria@kowasa.com

www.kowasa.com

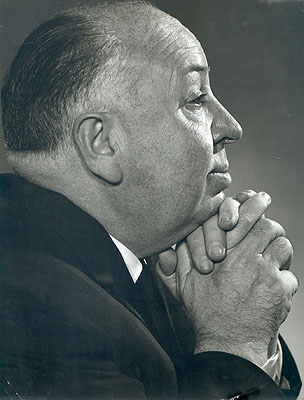

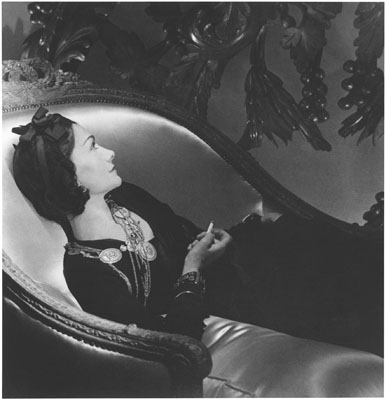

Tue-Sat 16:30-20:30

KOWASA gallery presents "The Vision of the Other: Modernity and the Photographed Face", a group show which attempts to define the way in which the human face was photographically constructed before its abolition by Postmodernism. The exhibition primarily offers a thorough insight into the history of portrait photography with a special emphasis on the shift of the portrait from being a mere "extension of the painted body" to being the photographic genre par excellence. At the same time it highlights the aesthetic and conceptual evolution of early portraiture from Pictorialism towards a modernist experimentation and subjectivity. The exhibition gathers more than 70 black and white prints whose protagonists are Coco Chanel, Ernest Heminway, André Breton, Marc Chagall, Dalí, Josep Pla, Andy Warhol, Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, Jean-Paul Sartre, Marilyn Monroe and others. Among the more than 50 participant photographers appear such internationally renowned names as Nadar, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Horst P. Horst, Edward Steichen, Josef Sudek, Arnold Newman, Man Ray; national photographers include Joan Colom, Francesc Català-Roca, Xavier Miserachs and Alberto Schommer. Throughout the exhibition ATELIERETAGUARDIA will be organizing portrait sessions using the technique of wet-plate collodion, one of the most emblematic photographic processes of the 19th century. ATELIERETAGUARDIA heliografía contemporánea is a platform for the study and practice of 19th century photographic technology. The advent of photography contributed to the re-evaluation of portrait art in regard to painting as, in the words of Samuel Morse, an "improved Rembrandt". Obtained through processes which required a long exposure and which resulted in many imperfections, the first portraits in the 19th century often suggested an attack on the vanity of their subjects. Following this, it is hardly surprising that the increasing aesthetic demands of the time very soon resulted in an army of portraits-makers at the service of retouching mastery. If the conviction that photography "robbed" the soul reigned in the 19th century, in the 20th century photography would become the soul's mirror. Under the impact of this idea which made a deep impression on the popular imagination, portrait photography was conferred the mission of capturing with sophistication the historic aura, whilst reflecting in its discourse the predominant social and cultural stereotypes. The poses of introspection, the overacting of the bourgeois fetishes and a harmonious representation of all the parts of the body constitute to some of the visual characteristics of this orthodox rhetoric of the portrait. Whereas the direct photographic take was supposed to provide sufficient data for recognizing oneself, the portrait –the supposed door to the soul– paradoxically ended up violating this principle by prioritizing a visual vocabulary that flaunted the pertinence of the individual into a social class. Pictorialism (late 19th century-early 20th) came to embody this ideology with its hymn to the inner being and its constant flirt with painting. Even if the status of the individual as agent of a social hierarchy was now fading in favour of a spiritual reflection that projected the emotional qualities of the person depicted, this did not mean to say that the Pictorialists were infringing upon the rules of the game –to the contrary, the deal between the socially imagined and the final representation was still preserved. This pictorialist concept remained firmly rooted in fine-art photography portraiture throughout the 20th century despite its ongoing ruptures and changes. Even the critical accomplishments of the European avant-gardes, which were widely popularized during the thirties and the post-war era, were adopted by portrait photography so as to construct a much more dynamic, persuasive discourse whose variants continued to fortify the mythologies and popular narratives of the time. Among the most characteristic cases is the portraiture of celebrities and actresses, whereby face and body were shaped in accordance to the myth. Likewise, the portraits of public personalities –politicians and artists–are enveloped by means of obsequious poses that associate them irrevocably with their respective names. Here, more than ever, the face turns into a public affair. In the meantime, with the introduction of hand-held cameras, the naturalization of poses and snapshot culture were gaining terrain. In the twenties, the avant-gardes denounced the mystic ambition of discovering what lay behind the face, and instead began to pursue aesthetic experimentation. In this new way of looking, according to which, in the words of László Moholy-Nagy, "each pore, wrinkle or freckle has its importance", the goals were quite distinct: the time had arrived to become definitively divorced from painting, to celebrate the inherent properties of photography –the camera eye, the negative and the positive. It was time to push aside the classist mise-en-scène and focus on a much more abstract and geometric representation of the external world. This experimentation with the photographic medium included over-exposures, formalism, special angles, close-up, and photomontage. Another important element of modernist portraiture in its most mature phase is the insertion of psychoanalysis and Freudian theories in its visual discourse. If the orthodox portrait propagated the unity of identity, these theories, first adopted by the Surrealists and the artistic circles linked to them, reinvented the face as something superficial, planting evidence for the duality between the person and their "persona", namely the masquerade one constructs for others –that is to say the polarization between the ego, the super-ego and the eradicated social image. For its part, direct photography was expressing its scepticism before the subject, under the decisive influence of the Marxist theories which advocated the consciousness of a social being. The debate became intensified after the second-world war. Portrait photography came out of the studio for good, capturing its subjects in poses of apparent informality within their natural environments –the artist in his studio, the composer beside his piano, the writer among his books, and above all, the photographer with his camera. Faces captured with carelessness demystified the system and the established social imagery by establishing an iconology of social synecdoche. Snapshot and candid street photography broke the complicity among the sitter and the photographer, and dynamized the traditional conception of the portrait. The problem now shifted to what Barthes has described as the battle of two identities with distinct domains: on the one hand, there is the photographer-voyeur, and on the other the photographed subject which elaborates its social masquerade to back up its image. In this new age, rather than being the "mirrors of the soul" of the sitters, portraits reflected the personality of the photographer. This ongoing rupture of the portrait as a unity accepted ambiguity and humour at the time of representation. The modernist faith concerning myth still persisted, although, at this time it was not projected by the external world but instead, by the author and his camera. It would not be long before the gaze turned its back on it. In the early seventies, the definitive "rupture of the mirror" would cause the final abolition of both implicated parts, the sitter and the "auteur" behind the camera.