Contacts for the work of Ute Behrend |

|---|

News of Ute Behrend |

|---|

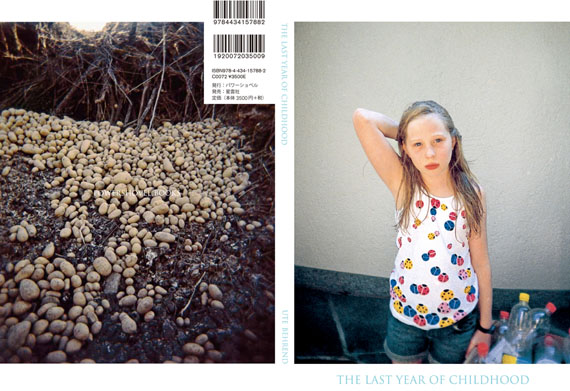

Ute BehrendTHE LAST YEAR OF CHILDHOOD POWERSHOVEL.BOOKS Japan.

Price: ¥3,675

Code: 9119

Size: 169 x 248 cm

ISBN: 978-4-434-15788-2

More info: Special Site

Order / bestellen : amazon.co.jp

|

Biography of Ute Behrend |

|---|

BIOGRAPHY 2011 The last year of childhood (Artists' book), publisher: POWERSHOVEL.BOOKS, Tokio/NewYork 2009 The door behind the wall | project with handicapped and not handicapped inhabitants of the Dr. Dormagen-Guffanti foundation, Cologne; Germany 2008 - 2009 Teaching assignment, college of higher education Bielefeld; Germany 2008 Zimmerpflanzen (Artists' book), publisher: Snoeck Verlag, Cologne; Germany 2007 Teaching assignment for Visual Communications, Merz Akademie, Design Academy Stuttgart; Germany 2006 Mermaids, Videos Galerie 11, in the Gruner + Jahr publishing house, Hamburg; Germany 2005 Teaching assigment, college of higher education Voralberg; Austria Märchen, Fairy Tales (Artists' book), publisher: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter König, Cologne; Germany 2004 Observer and Indoor Plants (Booklet) latent, aristotelean mimesis within the thriller genre publishing label: www.bold-dvd.de 2002 Art goes School | state chancellery, Saarland; Germany 2001 kunstKöln special edition 1996 Girls, Some Boys and Other Cookies (Artists' book) publisher: Scalo Verlag, Zürich; Switzerland 1993 Diploma 1987 - 1993 Academic studies: Photo - Design University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Dortmund; Germany 1985 - 1987 Academic studies: Communikation Design University of Applied Sciences, Wiesbaden; Germany 1979 - 1982 Apprenticeship as a carpenter |

Texts about Ute Behrend |

|---|

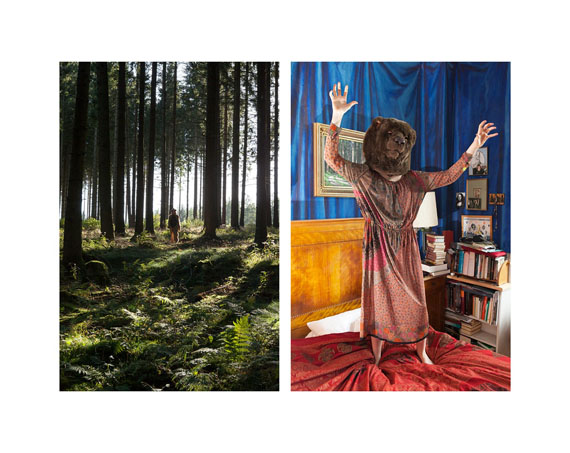

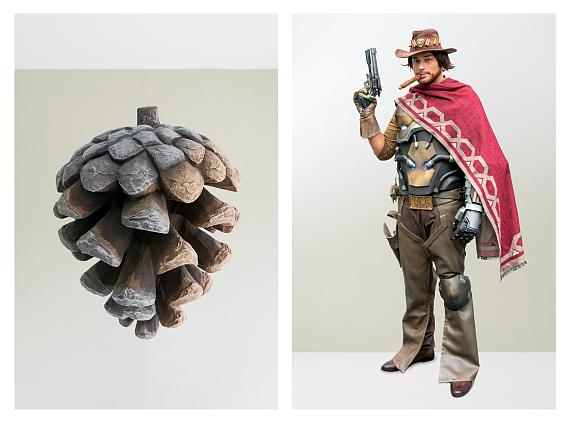

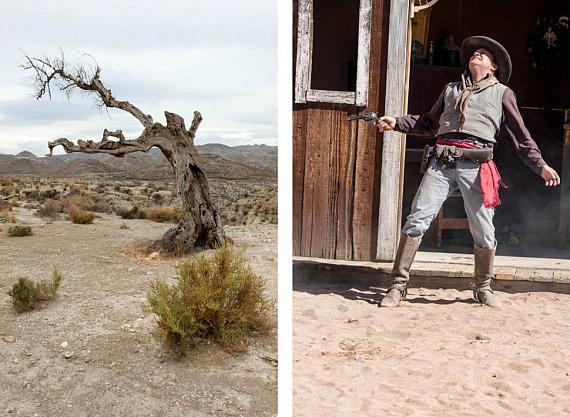

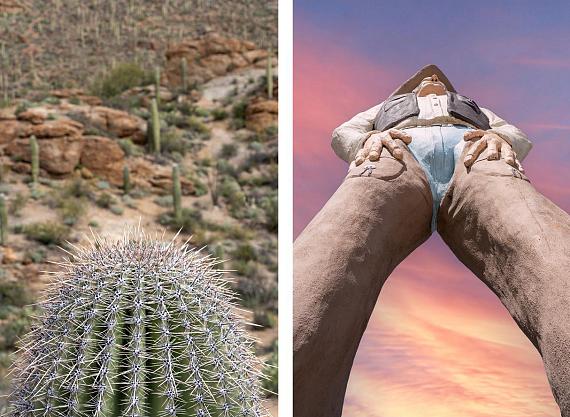

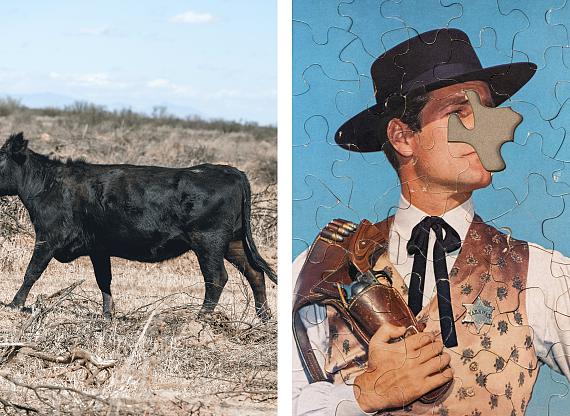

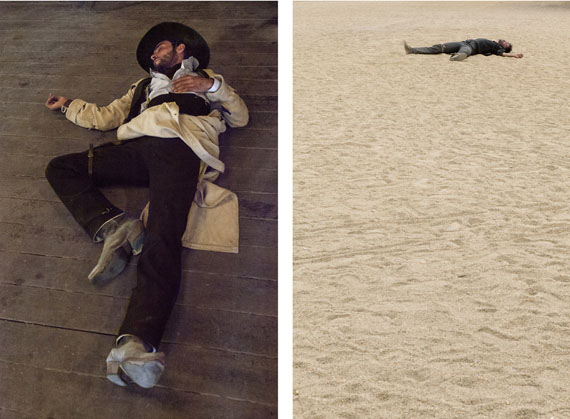

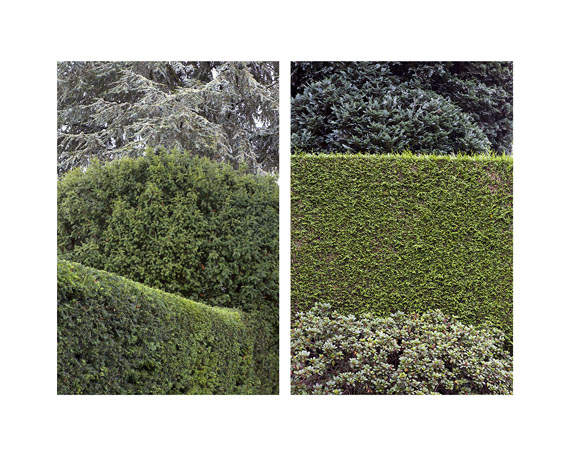

Christoph Ribbat One is the loneliest number »In photography«, says Jeff Wall, »the unattributed, anonymous, poetry of the world itself appears, probably for the first time«. Its beauty »is rooted in the great collage which everyday life is, a combination of absolutely concrete and specific things created by no-one and everyone, all of which become available once it is unified into a picture«.1 Actually, h… (more) Christoph Ribbat One is the loneliest number »In photography«, says Jeff Wall, »the unattributed, anonymous, poetry of the world itself appears, probably for the first time«. Its beauty »is rooted in the great collage which everyday life is, a combination of absolutely concrete and specific things created by no-one and everyone, all of which become available once it is unified into a picture«.1 Actually, he’s right. The »unattributed, anonymous poetry«, the »great collage«, all the »concrete and specific things«: these are what photography—unique, addictive, casual, potent, improvised photography—deals with and what it is derived from. It is what the photobook deals with and is derived from, this magical admixture of film, novel and family album, which only now we have really come to appreciate.2 However, it is strange to believe, as Wall apparently does, that the things, spaces and faces from everyday life have the capacity to be »unified into« a single picture. Even more remarkably, a significant movement within contemporary photographic art has distanced itself from the fantastic charm of the pictorial narrative and become more interested in the rather sober solitaires on the wall and the perspective from a safe distance. It is precisely the most prominent photographers, inundated with money and fame, who tend towards aristocratic minimalism. They labour on the uncluttered, gigantic single picture for the uncluttered, gigantic museum. Alternately, they devote themselves to the systematic sequence. The individual element is constructed as a—hrrumpf—serial phenotype: shopping centres, libraries, always viewed from the same angle, always in the same light. Even Jeff Wall ultimately doesn’t trust his much vaunted accident, preferring to stage his tableaux himself. In this way he creates disorder ordered by himself, including those concrete things and their unattributable poetry. All of this is astonishing because such artistic practises clearly differentiate themselves from the other, everyday, snapshot world of photography. They distance themselves, possibly consciously, from us, the lay public who very seldom perceive photographic images as monumental individual entities, mostly encountering them in pairs, as groups, in heaps: along the lines of before-and-after, this-is-me-here-and-this-is-me-there, look-at-this-and-look-at-that. Perhaps these free-range herds of images intimidate many a photographic artist because they threaten his sanitary method. In everyday life the simple bumps into the decorative, the delicate encounters the dangerous, the repulsive links arms with the delectable. Images generate narratives. They have firm sets of meanings. They have symbolic value. This is difficult to countenance if you view the photographic image as a mysterious monad, which, silent and perfect, doesn’t require anything around it but empty space (and plenty of it). Ute Behrend’s works are different, however. They come in twos. Always in twos. Instead of meticulously dissecting the dual components of what you see and what that might signify, Behrend infuses her series of images with both elements. She fears neither disorder nor decoration, neither ornament, children’s eyes, pink petals, turquoise dressing gowns, rubber plants, pierced nipples, rottweilers, nor pools of blood. She takes private photographs, but this is an undefinable kind of privacy, temporally localised as the present day, in a place situated somewhere between the city and country and vacation spots, of a generation between youth and mid-life. One’s eye oscillates between one and the other image. It compares, contrasts, combines, engendering in turn mini-narratives that start on the left and end on the right or start on the right and end on the left. Or they become long narratives encompassing several images—narratives that branch out, leaf, blossom. For goodness sake no stories, no plants—say the coolest minimalists. For goodness sake no minimalism, says Ute Behrend. You have to cope with proliferation. Photosynthesis, 6 CO2 + 6 H²O → C6H12O6 + 6 O2, the transformation of light into greenery that then spreads out over surfaces and grows into voids: nobody can deny that this is all part of the »great collage«. Therefore one really is the loneliest number, because it cannot do justice to disorder. One image wouldn’t be enough, a typological series would be too strict, a mise en scène too clinical. Ute Behrend’s video art also testifies to the power of this approach—perpetually split in two, as is her photographic work. At the start of her video »Mermaids«, for example, the sun is shining through a gap in the heavy, grey clouds pictured in the image on the left and in the image on the right, in front of a blank wall, a woman is singing a Harry Warden/Mack Gordon-Song, which one recognises from Chet Baker’s version (» …the more I see you, the more I want you / Somehow this feeling just grows and grows …«) and perhaps because this woman does this so well, singing so unpretentiously, as unpretentiously as Chet Baker himself, and because sometimes the sun really does pierce through the grey canopy in this fashion, as indeed everyone knows, and because the sound of the surf can also be heard on the soundtrack and children’s voices can be discerned discussing something and then fading into the distance once more, and because a bird suddenly flies in front of the clouds across the image and then disappears, and because all of this is the case, it seems for a moment as if nothing else exists apart from these clouds, the sound of the surf, the light, the song, the way it is being sung and the way the song is remembered, and the bird in flight and the bird that has flown and the voices and the quietness that follows. And at this point it becomes clear: true purism is the one that also incorporates the noise. It is the one that both shows what we see and what we remember: the voice and the rushing sound, the moment and its feedback. Ute Behrend’s photographic series allow you to experience this haptically, laying these combinations in your hands, in the photobook, the ultimate storehouse for what Jeff Wall calls »anonymous poetry«. Look right. Look left. Look left. One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do.3 1 Zitiert in: Kaja Silverman, »Totale Sichtbarkeit«. Jeff Wall: Photographs. Köln 2003. S. 97–117; hier S. 111. 2 Vgl.: Martin Parr und Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History, Vol. I & II. London 2004/2006; Andrew Roth, ed., The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century. New York 2001. 3 Aimée Mann, »One«. Magnolia: Soundtrack. Warner, 2000. CD (Text & Musik: Harry Edward Nilsson, 1968).� Christoph Ribbat Eins ist die einsamste Nummer »In der Fotografie«, sagt Jeff Wall, trete »die wortlose, anonyme Poesie der Welt zuerst, ja wahrscheinlich zum allerersten Mal zu Tage.« Ihre Schönheit wurzle »in der großen Collage, als die sich das tägliche Leben darstellt: jene[r] Kombination völlig konkreter und spezifischer Dinge, die, von allen und niemandem geschaffen, greifbar werden, sobald sie sich zu eine… (more) Christoph Ribbat Eins ist die einsamste Nummer »In der Fotografie«, sagt Jeff Wall, trete »die wortlose, anonyme Poesie der Welt zuerst, ja wahrscheinlich zum allerersten Mal zu Tage.« Ihre Schönheit wurzle »in der großen Collage, als die sich das tägliche Leben darstellt: jene[r] Kombination völlig konkreter und spezifischer Dinge, die, von allen und niemandem geschaffen, greifbar werden, sobald sie sich zu einem Bild fügen.«1 Er hat recht, tatsächlich. Die »wortlose, anonyme Poesie«, die »große Collage«, all die »konkrete[n] und spezifische[n] Dinge«: Von ihnen handelt, aus ihnen entsteht – einzigartig, süchtig machend, lässig, mächtig, improvisiert – die Fotografie. Und von ihnen handelt, aus ihnen entsteht das Fotobuch, diese magische Mischung aus Film, Roman und Familienalbum, die wir jetzt erst so richtig zu würdigen wissen.2 Seltsam ist es nur, daran zu glauben, dass sich die Dinge, Räume und Gesichter des täglichen Lebens, wie Wall es sagt, zu genau »einem Bild fügen« könnten. Noch bemerkenswerter ist, dass sich in der zeitgenössischen Fotokunst eine so bedeutende Strömung weg bewegt hat vom fantastischen Charme der Bild-Erzählung und sich eher für nüchterne Solitäre an der Wand interessiert und für eine Perspektive aus der sicheren Distanz. Gerade die prominentesten, mit Geld und Ruhm am meisten überhäuften Fotografen neigen zum aristokratischen Minimalismus. Sie arbeiten am aufgeräumten, gigantischen Einzelbild, das hervorragend in aufgeräumte, gigantische Museen passt. Oder sie widmen sich der systematischen Reihe. Das Einzelne wird als, hmpfh, Phänotyp konstruiert, der in der Serie hervortritt: Einkaufszentrum, Bibliothek, immer aus dem gleichen Blickwinkel, immer im gleichen Licht. Auch Jeff Wall schließlich traut dem von ihm gepriesenen Zufall nicht über den Weg und inszeniert seine Tableaus lieber selbst. So schafft er von ihm selbst angeordnete Unordnung, inklusive jener konkreten Dinge und ihrer wortlosen Poesie. Erstaunlich ist all dies, weil sich solche künstlerischen Praktiken eindeutig absetzen von der anderen, der alltäglichen Schnappschusswelt der Fotografie. Sie entfernen sich, möglicherweise bewusst, von uns, den Laien, die fotografische Bilder eher selten als einzelne Prachtexemplare wahrnehmen und ihnen zumeist als Paaren, Gruppen, Haufen begegnen: à la vorher-nachher, hier-war-ich-dort-und-da-war-ich-da, guck-mal-dies-an-und-jetzt-guck-mal-das. Vielleicht erschrecken diese freilaufenden Bilderherden manch fotografierenden Künstler, weil sie die Sauberkeit seiner Methode gefährden. Im Alltag trifft das Simple auf das Dekorative. Das Zarte begegnet dem Gefährlichen. Das Widerliche verschränkt sich mit dem Süßen. Im Alltag ergeben Bilder Geschichten. Sie haben feste Bedeutungen. Sie haben symbolische Kraft. Das ist schwierig zu ertragen, wenn man jemand ist, der das fotografische Bild als geheimnisvolle Monade begreift, die, schweigsam und perfekt, nichts um sich braucht als leeren Raum (und davon reichlich). Ute Behrends Arbeiten sind allerdings anders. Sie kommen zu zweit. Immer zu zweit. Das, was man sieht und das, was es bedeuten könnte: Behrend legt beides in ihre Bilderserien hinein, statt es sorgsam auseinander zu sezieren. Sie hat weder vor Unordnung Angst noch vor Dekoration, Ornament, Kinderaugen, rosa Blüten, türkisen Morgenmänteln, Gummibäumen, gepiercten Brustwarzen, Rottweilern, Blutlachen. Sie fotografiert im Privaten, aber es ist ein undefinierbares Privates, in einer Zeit circa heute, in einem Raum zwischen Großstadt und Umland und Urlaub, einer Generation zwischen Jugendlichkeit und der Mitte des Lebens. Der Blick schwankt immer zwischen dem einen und dem anderen Bild. Er vergleicht, kontrastiert, vermengt. So entstehen Minigeschichten, die links beginnen und rechts enden oder rechts beginnen und links enden. Oder zu längeren Geschichten werden, über mehrere Bilder hinweg – zu Geschichten, die Zweige treiben, Blätter, Blüten. Bloß keine Geschichten, bloß keine Pflanzen, sagen dann die kühlsten Minimalisten. Bloß kein Minimalismus, sagt sich Ute Behrend. Gewucher muss man aushalten. Photosynthese, 6 CO2 + 6 H²O → C6H12O6 + 6 O2, das Umwandeln von Licht in Grünzeug, das sich dann über die Flächen legt und durch die Leere wächst: Keiner kann so tun, als gehöre das nicht zur »großen Collage«. Deshalb ist Eins die einsamste Nummer, tatsächlich, weil sie der Unordnung nicht gerecht wird. Ein Bild wäre zu wenig, eine typologische Serie zu streng, eine Inszenierung zu klinisch. Die Kraft dieses Ansatzes belegt auch Ute Behrends Videokunst, stets zweigespalten, wie ihre fotografischen Arbeiten. Zu Beginn ihres Videos »Mermaids« etwa strahlt im linken Bild die Sonne durch ein Loch in den bleiernen Wolken und im rechten singt eine Frau vor einer nackten Wand einen Harry Warden/Mack Gordon-Song, den man quasi nur von Chet Baker kennt (»…the more I see you, the more I want you / Somehow this feeling just grows and grows…«) und vielleicht weil diese Frau das so gut, aber unprätentiös singt, fast so unprätentiös wie Chet Baker selbst, und weil die Sonne wirklich manchmal so durch das Grau sticht, man weiß es ja selbst, und weil über die Tonspur noch das Meer rauscht und erst Kinderstimmen irgendetwas besprechen und sich dann entfernen, und weil plötzlich ein Vogel vor den Wolken durch das Bild fliegt und dann nicht mehr da ist, weil all das so ist, scheint es für einen Moment so, als würde es nichts geben außer diesen Wolken, dem Rauschen, diesem Licht, und dem Lied, wie es gesungen wird, und dem Lied, wie man es erinnert, und dem Vogel im Flug und dem geflogenen Vogel und den Stimmen und der Stille danach. Und hier wird klar: Der wahre Purismus ist der, der den noise mit aufnimmt. Der also das, was wir jetzt sehen, genauso zeigt wie das, was wir erinnern: die Stimme und das Rauschen, den Augenblick und sein Feedback. Ute Behrends fotografische Reihen machen das haptisch erfahrbar, legen diese Kombinationen in deine Hände, im Fotobuch, dem Speicher schlechthin für das, was Jeff Wall »anonyme Poesie« nennt. Schau nach rechts. Schau nach links. One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do.3 1 Zitiert in: Kaja Silverman, »Totale Sichtbarkeit«. Jeff Wall: Photographs. Köln 2003. S. 97–117; hier S. 111. 2 Vgl.: Martin Parr und Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History, Vol. I & II. London 2004/2006; Andrew Roth, ed., The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century. New York 2001. 3 Aimée Mann, »One«. Magnolia: Soundtrack. Warner, 2000. CD (Text & Musik: Harry Edward Nilsson, 1968).� |